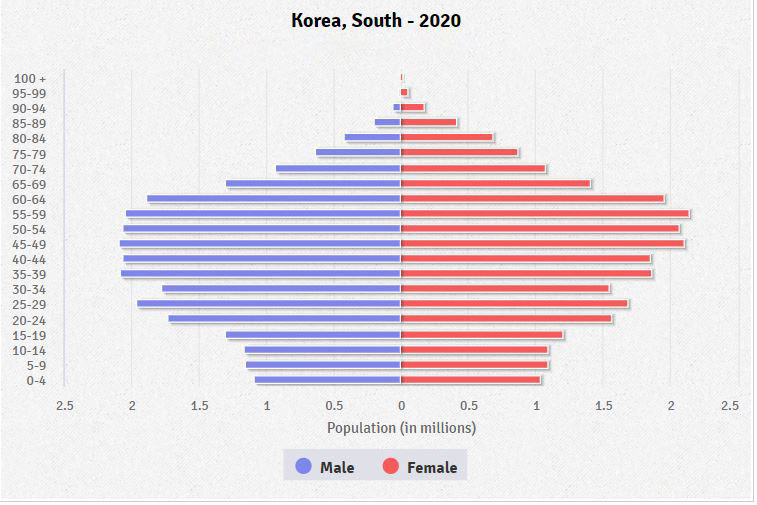

South Korea has been struggling with a declining birth rate for years as it belongs among the most rapidly aging societies in the world. This problem can be also seen as a close connection to low acceptance of migrants in the country. The dividing opinion on foreigners comes from deep-seated monoculturalism and from the experiences that people know from the war and occupation in the past. The history of repeated invasions and unfulfilled promises continues to strengthen mistrust and discrimination towards other nations and cultures. Migration policies became heavily discussed topic in the country during the Yemeni crisis in 2018 and now during the movement of people from Afghanistan connected to Taliban invasion. Linked to South Korean policies is also the topic of marriage migration in the country, mostly of females from nearby countries in high numbers [1].

The country is weighted down with the highest rate of unemployment in recent years and with the raising socio-economic inequality. All these problems relate to natural dissatisfaction of the young population in the country. Problems connected with xenophobia and islamophobia are spread among the population as there was limited contact with people outside of South Korea. The interactions between native South Koreans and immigrant communities are still rare and unusual [1].

Findings of multiple researchers show that the majority of the South Koreans oppose welcoming refugees to their country. There is a slightly different opinion if the foreigners are people from North Korea, as it is believed that they are closer to sharing the same values and principles, which is an important factor of social acceptance [2]. Sharing Korean blood and cultural practices is considered as something that makes you a “true Korean” [3]. North Koreans are more likely to be granted South Korean citizenship and their assimilation is much easier than for non-Koreans. Although the South Korean government made some steps promoting multiculturalism and acceptance, the desire for ethnically homogenous South Korean society still prevails. The lessons about racial purity and blood-based nationhood have been removed from textbooks only recently [2].

As mentioned before, the contact with cultural outsiders was limited in the past, which only contributed to the spread of xenophobia in the country. Discrimination towards foreigners in this case is understood as a fear of unknown and past traumas [4]. Problems with Islamophobia sparked when Yemeni refugees came to seek shelter in 2018 due to civil war in their country. Their arrival was viewed as a threat to Korean women and to already weak economic conditions. Dissatisfaction then led to protests in the country [4]. The e-petition proposing to cancel grant of refugee status, through which people from Yemen in 2018 came to Korea, was signed by more than 700,000 people [1].

Yemen Crisis

The refugee crisis in South Korea began in 2018 with the arrival of 500 Yemeni citizens on Jeju Island, as they used the visa-free entry system [5]. This step sparked controversy through the country. The perception of refugees was shaped by the refugee crisis in Europe, which was associated with an anti-refugee attitude in most countries. As a way of trying to justify a xenophobic response towards refugees, people used a number of high-profile crimes committed at that time by Muslim refugees in Europe, portraying Muslims as criminals and threat to society. Since then, there have been many public calls for refugees to return to Yemen, not taking into consideration the ongoing civil war and health crisis persisting till this day. South Korea have been trying to give its citizens the feeling of being heard but at the same time also fulfil binding international commitments towards refugees [6].

Yemeni civil war, which is ongoing since the September of 2014, puts the country on the list of the most dangerous places to live in. The arrival of refugees from Yemen was unexpected and it started the wave of fear among the nation. Refugees were viewed as a threat to society which triggered calls for the abolition of the visa-free system. The attitude of South Korea towards Yemeni crisis could be described as inconsistent, as there was a gap between the promises mentioned in Refugee Convention, which talked about open willingness to accept refugees, and the actual accommodation and assimilation of mentioned refugees. South Korea is the first Asian nation that adopted a refugee act [6]. Sadly, this is not coincident with the rate of granted refugee status. Between the years 1994 and 2020 only around 1,5% of all applicants received the status, which is the lowest rate from all developed countries [7]. Governments of Korea and Jeju decided to keep the visa-free system for economic reasons, but they implemented narrow policy, which allows them to exclude Yemenis from the visa-free list.

Suddenness and the high number of refugees that came to South Korea got widespread media coverage. This started the discussion between the terms “real” and “fake” refugees. It was accompanied by the rumors that these fake refugees are economic migrants. Because of that, government decided to do background checks, tough procedures against those who over-stayed visa period and strengthening identity verification. Many argue that division between real and fake refugees should not be on top of priority list and it should be replaced with providing all with protection and assistance and transformation that would bring international peace. The later revised this process, shortened the period of examination for refugees and created a new refugee agency [6].

Afghanistan Crisis of 2021

The return of Taliban after the US-led occupation was a title for many weeks in media all over the world. Shockingly fast advance across the country was finished with capturing Kabul in the summer of 2021. Countries are now leading discussions on how to proceed and deal with the new regime. The conflict has killed tens of thousands of people and many more are displaced. How the Taliban plans to govern the country is not completely known, but many violations of human rights have been reported since the August of this year [8].

South Korea welcomed 378 Afghans who have worked for South Korea’s embassy and other facilities and labeled them as “persons of special merit” instead of refugees, which sparked controversy and discussions about the reasons for the change. They were given short-term visas and they were granted the option to switch to long-term visas, that would enable them to work in the country [5].

What is the difference between refugee and “person of special merit”? Analysts agreed that there are only small differences, but the biggest one is probably the change in the name. Some refugee advocates believe that this wasn’t correct step as it reduces the granting of refugee status “which should be granted according to South Korea’s obligations under international human rights law, to a medal awarded to those who have done well for the government rather than being granted to those who are clearly at risk of persecution”, which applied for these Afghans as they worked in the institutions connected to South Korea [5] [9].

The Korean public showed unexpected and overwhelming support for the settlement of the Afghan ‘special contributors’. The reasons for this may vary, but the most probable one is that conflict in Afghanistan is more known compared to the Yemeni civil war, which was even one of the reasons why the “real/fake” refugee debate has not been even mentioned in this case. The other fact that helped the wider acceptance of Afghans was that the refugees were mostly families, consisting of women and children, while during Yemeni crisis thy predominantly consisted of men [5].

This change in South Korean society cannot be taken as a dramatic shift in their views of refugees. There is still prevailing negative opinion on refugees and their stay in South Korea. Government had to change the name of the group that came from Afghanistan multiple times, before settling to “special contributors”, as only 9 foreigners since 1948 were granted the name “persons of special merit” [5].

Bachelor Surplus and Marriage Migration

Marriage migration, meaning the entry of foreign spouses of Korean nationals, has been a major route, together with unskilled labor migration to Korea. Specific exceptions apply to this group, unlike most other types of migrants, marriage migrants are encouraged to settle permanently. A growth in marriage migration, mostly of female migrants, is a major part of Korea’s migration processes. South Korea came with a comprehensive set of policies targeted specifically at marriage migrants and their families [10].

Before the 2000s, international marriage was rare in Korea, as the society is based on homogeneity, marriage with someone outside of South Korea was judged and uncommon. The reproductive crisis and low birth-rate have been sensitive issues in Korea, as failure to marry is stigmatized, although there has been an improvement in understanding this issue now. These problematic standards set upon unmarried people even brought reports of abuse against migrant women, taking things to extremes in the form of forced marriages.

What caused this marriage migration route was so-called ‘bachelor surplus.’ Commonly sex-selective abortion was practiced in the country and the consequences of preference for sons led to a serious imbalance [10]. Conditions in social and economic sector improvement which also contributed to the low birth-rate and delaying marriages. Government eventually established policies that targeted marriages of migrants and came with ‘Multicultural Families Support Act.’ Its aim is to help these families to improve their life and integrate into society more easily. These policies targeted specifically marriages where female migrant marries Korean men. They also ensure that in the future the children of migrants and their failure in adaptation will not be an economic or social problem in the Korean future. The government even amended law in favor of marriage migrants, as the rules for granting citizenships are easier for them. For example, the waiting period which makes them eligible for claiming citizenship has been shorten for them. Marriage migrants, therefore, represent rather atypical position in Korea where anti-settlement is the prevailing goal of migration policy. Most of marriage migrants come from nearby Asian countries, mostly China, Vietnam and Japan [10] [11].

To make sure that there is a balance between the numbers of men and marriage-age women the government will eventually need to rely on and support stable flows of migrants. The bilateral relations will be affected by the way South Korea will treat its migrant populations and international reputation in global governance organizations can be changed concerning this issue. South Korea’s demography is undoubtably changing, now around four percent of the population are foreigners. With slow transition into a multicultural society avoiding social conflict, accepting refugees, addressing discrimination, exclusion and marginalization will probably be among top goals for government concerning migrants. “The influx of foreign workers and brides illustrates the growing predominance of intra-Asian migration as opposed to the early postwar decade in which the primary Korean migrant flows were to North America”[12].

Future of South Korea

“As Asia further transforms itself as a region of growth and prosperity, intra-regional immigration is likely to increase even more. The increasing economic and cultural integration of the Asian region will facilitate this trend” [12]. The government will probably try to promote less restrictive immigration laws and programs, even though its attempts until now have been only limited [1]. Other countries provided examples for South Korea on accommodation of larger numbers of refugees and providing those who fled their homes with support and aid that they needed. A year after Yemeni refugees entered the country, Korean government, together with specialized institutions put more effort into assisting migrants and integrating them into the society, however that solution is not a lasting one and will need many renovations in the future [6]. While thinking about demographic assumptions, which say that the retirement age in Korea will be deferred until age 80 and decline in working-age population of 26 percent from 2030 to 2050, Korean government also must think about how low refugee acceptance is linked to bilateral relations and international reputation in global organizations, especially those that put their focus on human rights [3].

Reference

[1] What Influences South Korean Perceptions on Immigration? (2020, October 5). The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/what-influences-south-korean-perceptions-on-immigration/

[2] Survey: South Koreans Oppose a More Open Refugee Policy. (2020, June 8). The News Lens. Retrieved from https://international.thenewslens.com/article/136149

[3] Draudt, Darcie. „South Korea’s Migrant Policies and Democratic Challenges After the Candlelight Movement.“ On Korea: Academic Paper Series 2019 13 (2019).

[4] Mahmoudi, Kooros M. „Rapid decline of fertility rate in South Korea: causes and consequences.“ Open Journal of Social Sciences 5.7 (2017): 42-55.

[5] Afghanistan Crisis Reignites South Korea’s Refugee Debate. (2021, October 2). The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/afghanistan-crisis-reignites-south-koreas-refugee-debate/

[6] Kwon, Jeeyun. „South Korea’s ‘Yemeni Refugee Problem,’.“ Middle East Institute 23 (2019).

[7] In South Korea, opposition to Yemeni refugees is a cry for help. (2018, September 13). CNN. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2018/09/13/opinions/south-korea-jeju-yemenis-intl/index.html

[8] Taliban are back- what next for Afghanistan? (2021, August 30). BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-49192495

[9] South Korea designates arriving Afghans as ‘persons of special merit’. (2021, August 26). The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/26/south-korea-designates-afghan-arrivals-as-persons-of-special-merit

[10] Kim, Gyuchan, and Majella Kilkey. “Marriage migration policy in South Korea: Social investment beyond the nation state.” International Migration 56.1 (2018)

[11] Seol, D-H., Kim, Y-T., Kim, HM., Yoon, HS., Lee, H-k., Yim, KT., Chung, K., Ju, Y. and Han, G-S., 2005, “Survey on Female Marriage Migrants and Welfare and Health Policy Measures”, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs of Korea.

[12] Kim, Andrew Eungi. „Demography, migration and multiculturalism in South Korea.“ The Asia-Pacific Journal 6.2 (2009).