For over two decades, the United States has been fighting an elusive epidemic that has grown into a serious Fentanyl crisis. The number of fatalities is increasing at an alarming rate every year, setting new records. The demand for the drug is on the rise, leading to transnational organized crime supplying it in massive quantities. The international nature of the crisis makes it challenging for authorities to tackle. So far, it has proven to be mostly ineffective, both domestically and internationally.

The Third Wave

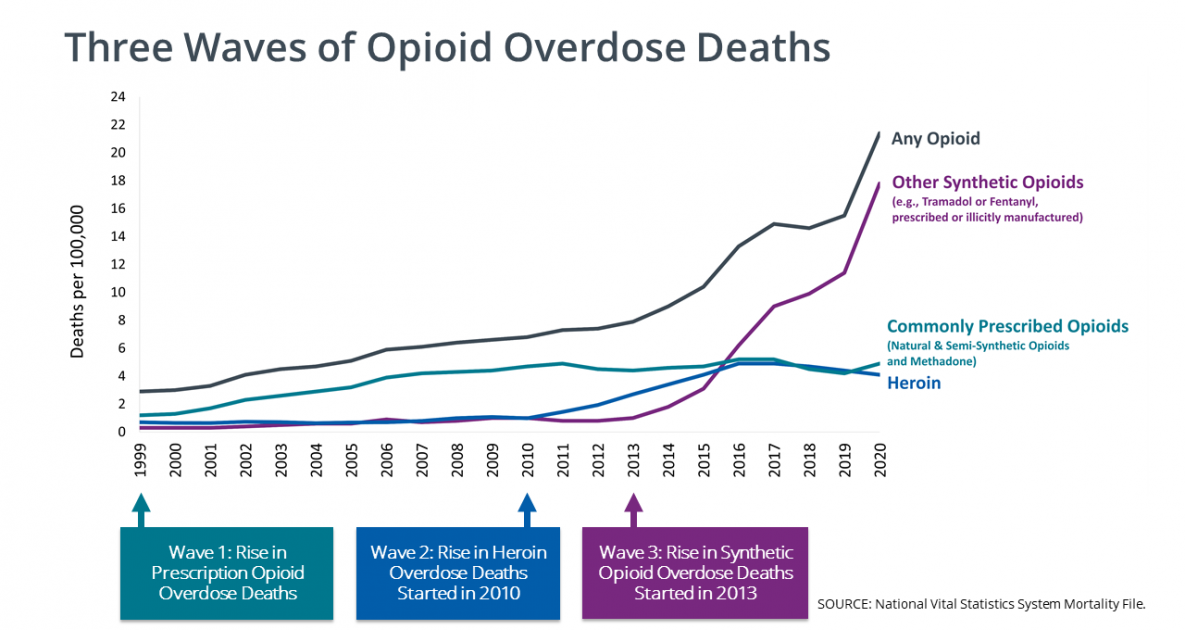

The fentanyl crisis is a nationwide epidemic that originated from a prescription-based usage of opioids and spread into misuse, addiction, and overdose deaths from illicit synthetic opioids. It is a complex issue that follows a gradual societal change rooted in the 1980s and 1990s when opioids became available as a treatment option in health care. [1] First used as a short-term pain relief agent after surgeries and for terminal conditions, it soon became a standard tool to manage chronic pain of any kind. [2] [3] Overprescribing, aggressive marketing, and a false assumption about the non-addictiveness of opioids played a major role in the unfolding epidemic. [4] Subsequently, the usage has spiralled into a devastating nationwide trend. [5] The first wave, fuelled by prescriptions, led to a rise in heroin addiction, creating the second wave. [6] Synthetic opioids came shortly after and swept the country into a severe crisis. [7]

The ongoing epidemic is caused by a large surplus of illicit supply of synthetic opioids, with fentanyl contributing to most of the fatal and nonfatal overdoses in the US today. [7] [8] [9] The main threat is posed by illegally made fentanyl substances, termed illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF). In 2013, the production and distribution of IMF skyrocketed and filled the entire illicit drug market. [10] Historically, positive supply shocks have been recorded to induce drug epidemics with disastrous consequences. [7] IMF is usually not the drug the users seek; hence, many are not even aware they are consuming it. [11] Many consumers are teens who have little or no knowledge about the danger of fentanyl. [12] [13]

For its heroin-like effect, extreme potency and cheap production, the IMF is often added to other drugs in various forms, including heroin, cocaine, MDMA, methamphetamine, and many others. [9] The concentration of fentanyl in other illicit drugs varies, making it unpredictable and substantially increasing the risk of overdose. [11] Just 2mg of IMF is deadly, the equivalent of a grain of sand. In comparison, a lethal dose of heroin is 100mg. [14] Therefore, adulterated illicit drugs and counterfeit pills can induce sudden respiratory depression and quick death. [15] According to the CDC, in 2022, there were 109,680 deaths from drug overdose in the US, making it the new record. [16] Opioid-related overdoses accounted for 72.7 %, i.e., 79,770 deaths. [17] In comparison, in the same year, roughly 245,000 were reported to have died from COVID-19 in the US. [18] Every day, more than 100 people die from opioid overdose; annually, it kills more people than car crashes or gun violence. The overall life expectancy in the US has declined by three years due to the epidemic, reversing a half-century trend. [19] [20] [21] [22]

The crisis has far-reaching negative consequences for the entire nation. It has been linked to increased crime, both violent and non-violent, and contributed to a broader spread of hepatitis C and HIV. Consequently, it creates pressure on law enforcement and the healthcare system. The toll of the epidemic is felt across every sociodemographic group and heavily burdens vulnerable populations, such as the economically disadvantaged. [23] The scale of the crisis makes it a challenge to the US economy and a threat to national security. [24]

Supply and trafficking of synthetic opioids

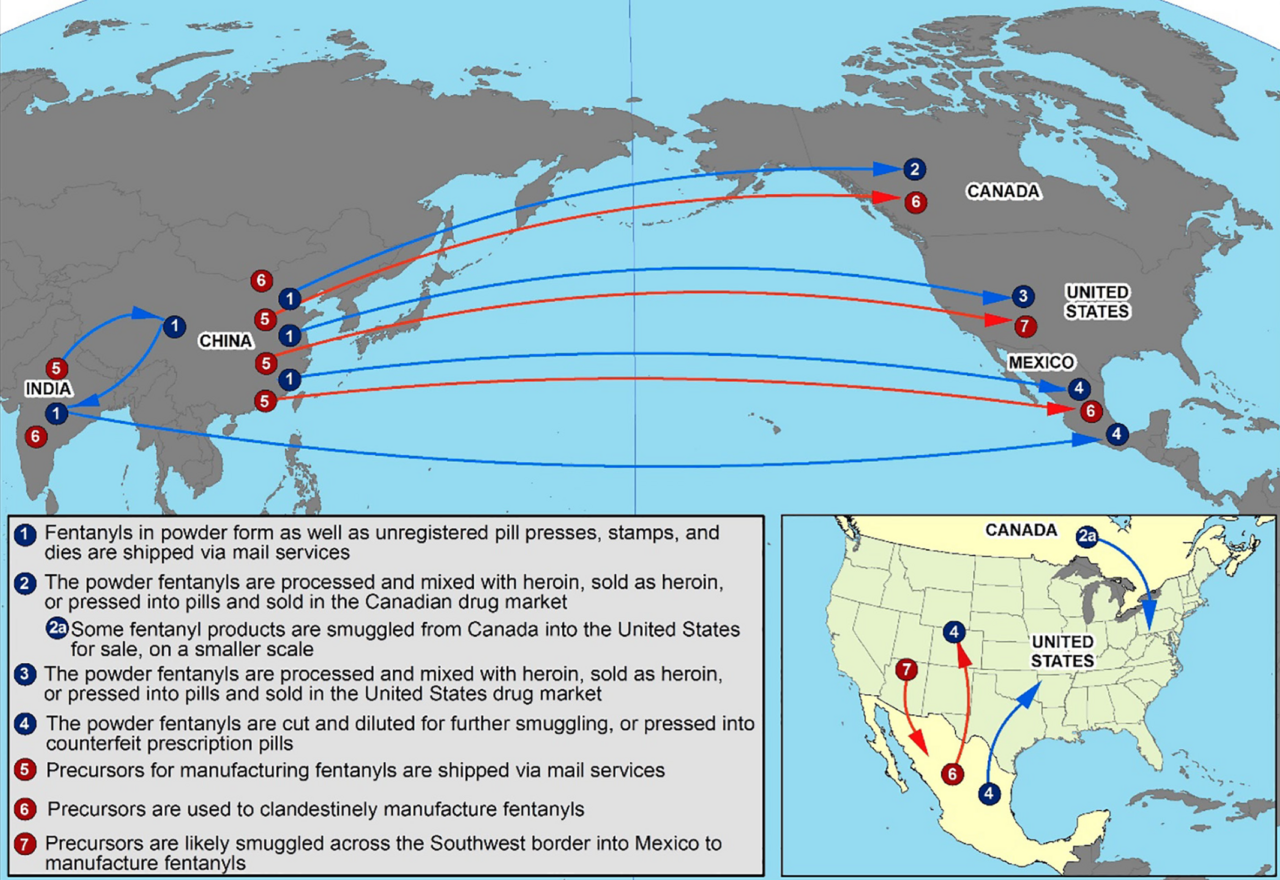

Unlike the prior fentanyl outbreaks, today, almost all of IMF is imported. [25] According to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the primary source of the IMF is China. From there, it is routed mainly through Mexico, or to a lesser degree Canada, into the US. [26]

China is by far the biggest supplier of synthetic opioids (India being the second). It is a harbour for thousands of chemical and pharmaceutical facilities that are poorly regulated and monitored. Since fentanyl is not widely used there, it falls under little scrutiny by the authorities. [27] [28] Exporters use increasingly sophisticated methods to conceal the operation, for example, exploiting mailing companies, mislabelling shipments, and creating new unregulated chemicals. All of which allows them to evade detection and move the product in enormous quantities. [28] [29] [30]

Fentanyl and its analogues and precursors, as well as fentanyl-laced products, are then shipped across the ocean. [29] [31] The subsequent trafficking is considerably complex. The export is diffused through smaller distributors and criminal organizations across the US, Mexico, and Canada, each operating individually. [28] [29] Equipment like pill pressers and materials for producing IMF can be easily obtained from China. [29]

A substantial part of synthetic opioids and precursors are first sent to Mexico. Large drug trafficking organizations (DTOs), namely cartels, synthesize fentanyl from precursors, manufacture opioid pills, and adulterate other drugs with IMF. The main buyers and smugglers are the Mexican cartels; they are primarily responsible for the increased availability of fentanyl in the US. [25] [26] [27] Two major DTOs are involved in the trafficking of IMF – Sinaloa, the most active supplier, and Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG). The main channel of IMF transportation to the states is through the southwest border via vehicles, as much as 95% of which go unscreened. [32]

The cartels dominate the whole drug trade in the US through clandestine labs in Mexico and a web of distribution cells in cities across the US. [33] [34] [35] IMF is highly profitable for cartels. Unlike other illicit drugs, it is easy to produce, inexpensive, potent, highly addictive, and difficult to track. Supposedly, cartels can gain revenues up to 350 times higher by adulterating other substances with IMF. For narcotraffickers, fentanyl is today what cocaine was in the 1980s: the hottest cash-generating product. [36] [32]

The inherently intricate structure of trafficking and the involvement of transnational criminal organizations make it quite distinct from other illicit drug trades. [28] The main difference is the change of focus from producers to low-level distributors and importers. Heroin, for example, requires significantly more time, space, and personnel to cultivate and process; hence, production is a major part of the trade. Fentanyl, on the other hand, can be quickly and easily synthesized. Thousands of farmers, cultivators and extractors can be replaced by a few chemists and small labs, producing IMF in just a few days. So, most of the trade and revenues shift to the side of distribution and trafficking instead. [37] [38]

For that reason, there is a possibility that synthetic opioids will lead to a collapse of the heroin trade in North America, Europe, and Russia. The global decline of the heroin market would potentially affect major opiate producers, namely Afghanistan, whose government relies on the poppy trade revenues. Such changes could create unpredictable consequences for the viability of the Taliban rule. [37] Therefore, the consequences of the fentanyl crisis can have a severe impact on other countries around the world.

Combating the Crisis Domestically

In 2022, the DEA seized over 379 million potentially deadly doses of fentanyl, enough to kill every American. [39] The US government has various strategies to restrict the flow of IMF to the states. Domestically, the US has been following a rather conventional approach. For decades, a punitive strategy of the „War on Drugs“ has been the essence of the country’s drug policy. [40] [41] Primarily by emphasising law enforcement and the penal system as a solution to the crisis. The most significant changes have been made in jurisdiction by implementing harsher punishments for possession and use. [24] [40] However, that has yielded little positive results while being considerably expensive. [42] Billions of dollars have been spent to crack down on drug users, leading to overcrowded prisons and overwhelmed justice system [42] [43] [44]. Contrary to such a strategy, evidence suggests a more liberal approach to decriminalisation and public health (e.g., the Portuguese model) works better. [24] [45] [46]

The severity of the crisis in the US asks for a radical change in the whole domestic strategy. Countries like The Netherlands, Austria and Canada have embraced a liberal approach and cantered their drug policy around public health. Individual states vary in the degree of liberalism; some (e.g., Portugal) have adopted the most extreme version, relying solely on a health care system. Ultimately, the evidence demonstrates that the liberal approach is superior to the conservative one. It has been proven to be a solution to opioid epidemics in countries like Portugal and Uruguay. [41]

The so-called Portuguese Model Drug Policy (PMDP) focuses on public health rather than sanctions and a „zero tolerance“ policy. The underlying idea of PMDP is to separate drug use from the stigma that associates it with criminal and pathological behaviour. [47] [48] The PMDP encompasses expanding healthcare infrastructure and decriminalising use and personal possession (i.e., it is still prohibited but not criminally sanctioned). In turn, decriminalisation makes more funds available to be invested in harm-reduction and treatment practices. [42] Another important implication is that it allows people to access the treatment without fear of imprisonment. [40] The benefits of the new policy can be observed in Portugal, where a number of drug-related problems have been alleviated, including drug use and death rates. [48]

In the US, the effort made in the jurisdiction has not been matched in the public healthcare area. [40] Significant gaps in the US healthcare system contributed to unsuccessful responses to the issue. Treatment access, capacity and quality are limited in comparison to other countries. [49] Given the wide range of affected sociodemographic groups, the unattainability of such treatment can be seen as problematic. Of a staggering 2.2 million people with opioid use disorder, barely 1 in 5 of them receive treatment. [50]

Despite the growing evidence of the inefficacy of such punitive measures, the US has persisted in relying on them, even in the expanse of a health-based approach. [40] [41] Many experts voiced the need for a better public health strategy, which would include safe consumption sites, access to naloxone, and increased education about the danger of such substances. [51] [49] [52] [53] Evidently, the crisis is not subsiding; some even argue that the fourth wave of polysubstance overdose deaths has arrived. [54] To address the crisis effectively, the affected population should be offered treatment instead of punishment. [40] [55]

Combating the Crisis Internationally

On an international level, the US strategy consists of bilateral cooperation with Mexico and China based on an effort to crack down on IMF production and distribution. For example, in 2015, China added 116 synthetic chemicals to the list of controlled substances. Then, following the G20 summit in 2016, China has “committed to targeting U.S.-bound exports of substances controlled in the United States, but not in China.” [27] Banning fentanyl export to the US in 2019 was considered the most significant progress. Nevertheless, in the end, it was not much of a success because Chinese chemical and shipping companies began to sell precursors instead. New precursors and analogues are being made faster than either can be banned, regulated, or identified and are then sold as legal substances. [56] In September of 2023, the US added China to the list of the world’s major drug-producing countries, a step that China denounced. [57]

There is little transparency in China’s enforcement and regulation of domestic fentanyl production. According to some, it remains to be “fragmented and decentralized”. [57] Cooperation of law enforcement tends to be self-serving and highly selective. Vested interests influence associations between local governments and industry in the chemical trade. [57] The politically powerful pharmaceutical industry comprises over 5,000 firms, and many manufacturers and distributors keep operating illegally. US-China counternarcotic cooperation is, from the US perspective, inadequate. [58] While it yielded some results in the past, it will likely not change unless the overall bilateral relationship improves. [59]

Recently, there appeared to be a breakthrough in US-China cooperation. In November of 2023, US President Joe Biden met with his counterpart in San Francisco, where an agreement had been made to curb fentanyl production. [60] This time, Chinese President Xi Jinping committed to target specific chemical companies. [57] [61] Following the summit, a China National Narcotics Control Commission issued a warning that any person or firm participating in the manufacturing or sale of fentanyl may face serious criminal charges. [60] After years of halted counternarcotic cooperation, this might mark the most significant progress. Nevertheless, time will only tell if it proves to be effective. Allegedly, China has been attempting to control fentanyl production for years, but due to the challenges in the domestic regulation framework, it was not enough. According to some studies, a more coherent and unified governance and binding international convention on fentanyl control is needed. [62] The advance in US-China coordination may be a step in the right direction. However, a more significant reformation is most likely needed for an efficient and lasting change. [62]

Collaboration with Mexico has granted somewhat better results. States on both sides of the border have tried to work together to thwart fentanyl trafficking. According to the US Embassy in Mexico, the fight against DCOs is built on joint, sustained, and comprehensive efforts. [63] In 2008, the US implemented the Merida Initiative – a counternarcotic cooperation framework providing the Mexican government assistance of $400 million a year, including equipment and surveillance software. It signified a new dawn of war against drugs in Mexico. [64] [65] Throughout the years, the counternarcotic policy kept reshaping and changing, but not necessarily for the better. President López Obrador recently claimed that fentanyl is not made in Mexico, although there is little dispute about it. According to an expert on Drug Policy and Mexico Studies, Gary J. Hale, Obrador “has done little to provide viable solutions to fentanyl problem and shows no interest in cooperating substantially” with the US. [46] In the beginning of 2023, Reuters also revealed that the Mexican military might be altering the records about the number of laboratories they have uncovered. [46]

In November 2023, Obrador met with both Biden and Xi Jinping, where they agreed to deepen anti-drug cooperation. In recent months, Mexico has also joined a United Nations program that facilitates the sharing of intelligence about drug trafficking activities. Nevertheless, many are sceptical about Obrador’s commitment to counternarcotic cooperation. Some experts suggest that the countries lack a shared vision, and due to their divergent drug policy strategies, the cooperation will remain stagnant. [66] [67] Also, given that the presidential elections of both countries are coming next year, the positive changes could be only short-lived. [66]

There is certain scepticism about the effectiveness of the US-Mexican and US-China cooperation. Combating the crisis is tricky, as it requires international commitment. However, the countries do not seem even to have the same estimate of the crisis, let alone a coordinated action plan. Additionally, it is being hindered by other political motives and world events, like COVID and the war in Ukraine. Valid estimation of the crisis, acknowledgement of shared responsibility, and cooperation should be prioritized according to Arturo Sarukhan, a former Mexican ambassador to the US. [46] Subsequently, a global regulation under an international convention could provide a binding means for fentanyl control. [62]

Conclusion

The fentanyl crisis is a serious problem, one that has had a devastating impact on US society. So far, the crisis has not been addressed adequately. A new comprehensive strategy is necessary. Otherwise, fatalities will grow, and the epidemic will continue to spread. Instead of trying to impose fear of punishment on those who are suffering from an addiction, the US should consider offering them treatment. In the field of international supply control, some advances have been made. Nevertheless, the cooperation between countries lacks a shared commitment, and the solution to the crisis solely through supply seems unlikely. To that end, the most considerable progress could be achieved domestically through a more liberal approach.

Article reviewed by Klára Šubíková and Martin Machorek

Sources

[1] DeWeerdt, S. 2019. “Tracing the US opioid crisis to its roots.” Nature 573(7773): S10-S12. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-02686-2

[2] Portenoy, R.K., Foley, K.M. 1986. “Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: Report of 38 cases.” Pain 25(2): 171-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(86)90091-6

[3] Makary, M.A., Overton, H.N., Wang, P. 2017. “Overprescribing is major contributor to opioid crisis.” BMJ 359. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4792

[4] Volkow, N. D., Blanco, C. 2021. “The changing opioid crisis: development, challenges and opportunities.“ Molecular Psychiatry 26: 218-233. https://doi.org/0.1038/s41380-020-0661-4

[5] Porter, J., Jick, H. 1980. “Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics.” New England Journal of Medicine 302(2): 123. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198001103020221

[6] Muhuri, P.K., Gfroerer, J.C., Davies, M.C. 2013. “Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States.“ CBHSQ Data Review. Available from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DR006/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.htm

[7] Ciccarone, D. 2019. “The Triple Wave Epidemic: Supply and Demand Drivers of the US Opioid Overdose Crisis.” International Journal of Drug Policy 71: 183-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010

[8] Wilson, N., Kariisa, M., Seth, P., Smith, H. IV., Davis, N.L. “Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2017–2018. “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69:290–297. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4

[9] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Fentanyl Facts. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/fentanyl/

[10] Gladden, R.M., Martinez, P., Seth, P. 2016. “Fentanyl Law Enforcement Submissions and Increases in Synthetic Opioid–Involved Overdose Deaths — 27 States, 2013–2014. “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(33): 837-843. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a2external

[11] Friedman, J., Bourgois, P., Godvin, M., Chavez, A., Pacheco. L., Segovia, L.A., Beletsky, L., Arredondo, J. 2022. “The introduction of fentanyl on the US–Mexico border: An ethnographic account triangulated with drug checking data from Tijuana.”International Journal of Drug Policy 104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103678

[12] https://www.npr.org/2023/08/30/1196343448/fentanyl-deaths-teens-schools-overdose

[13] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/19/health/pills-fentanyl-social-media.html

[15] Han, Y., Yan, W., Zhang, Y. et al. 2019. “The rising crisis of illicit fentanyl use, overdose, and potential therapeutic strategies.”Translational Psychiatry 9(282). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0625-0

[16] National Vital Statistics System. Estimates for 2022 are based on provisional data. Estimates for 2015-2021. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_public_use_data.htm

[17] National Vital Statistics System. Provisional Data Shows U.S. Drug Overdose Deaths Top 100,000 in 2022. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fnchs%2Fproducts%2Fvsrr%2Fdrug-overdose-data.htm

[18] Ahmad, F.B., Cisewski, J.A., Xu, J., Anderson, R.N. 2023. “COVID-19 Mortality Update — United States, 2022.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72(18): 493-496. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a4

[19] Roppero-Miller, J.D., Speaker J. P. 2019. “The hidden costs of the opioid crisis and the implications for financial management in the public sector.” Forensic Science International: Synergy 1: 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsisyn.2019.09.003

[20] Kenneth, D. K., Murphy, S. L., Xu, J., Arias, E. 2017. “Mortality in the United States, 2016.” NCHS Data Brief 293:1-8. PMID: 29319473

[21] Center for Behavioral and Health Statistics and Quality. 2017. Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf

[22] More Powerful. “The Impact of Opioids.“ Available from https://www.morepowerfulnc.org/get-the-facts/the-impact/#:~:text=More%20than%20100%20people%20die,Addiction%20contributes%20to%20mass%20incarceration

[23] Maclean, J. C., Mallatt, J., Ruhm, Ch. J., Simon, K. I. 2022. The Opioid Crisis, Health, Healthcare, and Crime: A Review of Quasi-Experimental Economic Studies. Working Paper 29983, National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29983/w29983.pdf

[24] Klobucista, C., Martinez, A. 2023. “Fentanyl and the U.S. Opioid Epidemic.” Council on Foreign Relatons. Available from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic

[25] U.S. Drug Enforcement administration. 2020. Facts about fentanyl. Available from https://www.dea.gov/resources/facts-about-fentanyl

[26] US Drug Enforcement Administration. 2017. 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment. Available at https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/DIR-001-17_2016_NDTA_Summary.pdf

[27] O’Connor, S. 2017. Fentanyl: China’s Deadly Export to the United States. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Staff Research Report. Available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/USCC%20Staff%20Report_Fentanyl-China’s%20Deadly%20Export%20to%20the%20United%20States020117.pdf

[28] Whalen, J., Spegele, B. 2016. “The Chinese Connection Fueling America’s Fentanyl Crisis,” Wall Street Journal. Available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-chinese-connection-fueling-americas-fentanyl-crisis-1466618934

[29] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 2016. Counterfeit Prescription Pills Containing Fentanyl: A Global Threat. DEA Intelligence Brief. Available at https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/docs/Counterfeit%2520Prescription%2520Pills.pdf

[30] Howlett, K., Giovannetti, J., Vanderklippe, N., Perreaux, L. 2016. “A Killer High, How Canada got addicted to fentanyl.” The Globe and Mail. Available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/investigations/a-killer-high-how-canada-got-addicted-tofentanyl/article29570025/

[31] Armstrong, D. 2016. “‘Truly Terrifying’: Chinese Suppliers Flood U.S. and Canada with Deadly Fentanyl,” STAT News. Available at https://www.statnews.com/2016/04/05/fentanyl-traced-to-china/

[32] Schisgall, E. 2023. “Synthetic Opioid Trafficking.” Harvard Model Congress. Available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cb7e5637d0c9145fa68863e/t/637da85ce8010a49de161a92/1669179492924/HMC+2023+-+House+Judiciary+2.pdf

[33] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 2021. 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment. Available at https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/DIR-008-21%202020%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_WEB.pdf

[34] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 2019. 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. Available at https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/2019-NDTA-final-01-14-2020_Low_Web-DIR-007-20_2019.pdf

[35] Pardo, B., Reuter, P. 2020. Enforcement strategies for fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. Brookings Institution. Available from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/5_Pardo-Reuter_final.pdf

[36] Tung, G. 2020. “The Potential Threat of The Sinaloa Cartel to Canada Through Production And Transportation Of Fentanyl.”The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare 3(2):40-46. https://doi.org/10.21810/jicw.v3i2.2373

[37] https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/LM313.pdf

[38] Reuter, P., Pardo, B., Taylor, J. 2021. “Imagining a fentanyl future: Some consequences of synthetic opioids replacing heroin.”International Journal of Drug Policy 94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103086

[39] Milgram, A. 2023. Drug Enforcement Administration Announces the Seizure of Over 379 million Deadly Doses of Fentanyl in 2022. U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Available at https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2022/12/20/drug-enforcement-administration-announces-seizure-over-379-million-deadly

[40] Gottschalk, M. 2023. “The Opioid Crisis: The War on Drugs Is Over. Long Live the War on Drugs.” Annual Review of Criminology 6:363-398. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-030421- 040140

[41] Gearty, Julie L. 2023. “How to win a drug war. Replacing criminalization of substance use disorder with evidence based harm reduction strategies.” MA thesis. Johns Hopkins University. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/cd34ac18-cdb3-41dc-b4fc-0e9a2af79bae/content

[42] Whitelaw, M. 2017. “A Path to Peace in U.S. Drug War: Why California Should Implement The Portuguese Model for Drug Decriminalisation.” Digital Commons 40(1):81-113. Available at https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol40/iss1/2

[43] Ziedenberg, J., Schiraldi, V. 2003. “Costs and Benefits? The Impact of Drug Policy Imprisonment.” Justice Policy Institute. Available at https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/costs-and-benefits-impact-drug-imprisonment-new-jersey

[44] Owens, S. 2021. “Prioritizing Prison over Substance Use Treatment Costs Kansans Safety and Money.” Justice Center, The Council of State Gonvernment. Available at https://csgjusticecenter.org/2021/02/25/prioritizing-prison-over-substance-use-treatment-costs-kansans-safety-and-money/

[45] Ferreira, S. 2017. “Portugal’s radical drugs policy is working. Why hasn’t the world copied it?” The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/dec/05/portugals-radical-drugs-policy-is-working-why-hasnt-the-world-copied-it

[46] Sarukhan, A., Felbab-Brown, V., Brewer, S., Wayne, E. A., Hale, G.J., Alonso, A. 2023. “How Is the Opioid Crisis Affecting U.S.-Mexico Ties?” Latin America Advisor. Available at https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/how-is-the-opioid-crisis-affecting-u-s-mexico-ties/

[47] Rego, X., Oliviera, M. J., Lameira, C., Cruz, O. S. 2021. “20 years of Portuguese drug policy – developments, challenges and the quest for human rights. “Substance Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 16(59). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00394-7

[48] Slade, H. 2021. “Decriminalisation In Portugal: Setting the Record Straight.” Transform Drug Policy Foundation. Available at https://transformdrugs.org/assets/files/PDFs/Drug-decriminalisation-in-Portugal-setting-the-record-straight.pdf

[49] Krausz, R. M., Westenberg, J. N., Tai, A. M. Y., Fadakar, H., Seethepathy, V., Mathew, N., Azar, P., Philips, Schütz, Ch. G., Choi, F., Vogel, M., Cabanis, M., Meyer, M., Jang, K., Ignaszewski, M. 2023. “A Call for an Evidence-Based Strategy Against the Overdose Crisis.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437231188202

[50] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. “Use of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder in criminal justice settings.” SAMHSA. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep19-matusecjs.pdf

[51] Leitz, S. J., Bagley, S. M., Cook, A. J., Jones, Ch., Lawrence, D., Pearce, P. 2023. “Strategies to Reduce Harm: An Expert Panel Discussion on the Fentanyl Crisis.” The Permanente Journal 27(1): 3-15. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/22.176

[52] Irvine, M. A., Oller, D., Boggis, J., Bishop, B., Coombs, D., Wheeler, E., Doe-Simkins, M., Walley, A. Y., Marshall, B. D. L., Bratberg, J., Green, T. C. 2022. “Estimating naloxone need in the USA across fentanyl, heroin, and prescription opioid epidemics: a modelling study.” The Lancet Public Health 7(3): 210-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00304-2.

[53] Ivsins, A., Warnock, A., Small, W., Strike, C., Kerr, T., Bardwell, G. 2023. “A scoping review of qualitative research on barriers and facilitators to the use of supervised consumption services.” International Journal od Drug Policy 111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103910

[54] Freidman, J., Shover, Ch. L. 2023. “Charting the fourth wave: Geographic, temporal, race/ethnicity and demographic trends in polysubstance fentanyl overdose death in the United States, 2010-2021.” Addiction 118(12), 2477-2485. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16318

[55] Corcoran, Robert. “Out of Street and Into State’s Arms: An Answer for the Drug Crisis?” Student Works. Available at https://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2301&context=student_scholarship

[56] John, T., Xiong, Y., Culver, D., Rappard, A., Joseph, E. 2023. “The US sanctioned Chinese companies to fight illicit fentanyl. But the drug’s ingredients keep coming.” CNN. Available at https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/30/americas/fentanyl-us-china-mexico-precursor-intl/index.html

[57] Swanson, A., Bradsher, K. 2023. “U.S. Presses China to Stop Flow of Fentanyl.” The New York Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/15/business/economy/biden-xi-fentanyl.html#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20has%20issued,as%20“a%20malicious%20smear

[58] Felbab-Brown, V. 2022. “China and synthetic drugs: Geopolitics trumps counternarcotic cooperation.” Brookings. Available athttps://www.brookings.edu/articles/china-and-synthetic-drugs-geopolitics-trumps-counternarcotics-cooperation/

[59] Glaser, B.S., Felbab-Brown, V. 2023. “China’s Role in the US Fentanyl Crisis.” GMF. Available at https://www.gmfus.org/news/chinas-role-us-fentanyl-crisis

[60] The White House. 2023. “Redout of President Joe Biden’s Meeting with President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China.” November 15, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/11/15/readout-of-president-joe-bidens-meeting-with-president-xi-jinping-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china-2/

[61] Hunnicutt, T., Mason, J., Holland, S. 2023. “Biden, Xi’s ‚blunt‘ talks yield delas on military, fentanyl.” Reuters. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/biden-xi-meet-us-china-military-economic-tensions-grind-2023-11-15/

[62] Wang, Ch., Lassi, N., Zhang, X., Sharma, V. 2022. “The Evolving Regulatory Landscape for Fentanyl: China, India, and Global Drug Governance.” International Journal of Environmental Research And Public Health 19(4): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042074

[63] Salazar, K. 2023. The United States and Mexico Strengthen Together Global Efforts to Stop the Fentanyl Crisis. U.S. Mission to Mexico. Available from https://mx.usembassy.gov/the-united-states-and-mexico-strengthen-together-global-efforts-to-stop-the-fentanyl-crisis/

[64] Council on Foreign Relations. 2023. “U.S.-Mexico Relations.” Available at https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-mexico-relations

[65] U.S. Embassy & Consultations in Mexico. 2021. The Merida Initiative. Available at https://mx.usembassy.gov/the-merida-initiative/

[66] Wayne, E. A., Brewer, S., Hale, G. J., Manaut, R. B., Felbab-Brown, V. 2023. “How Well Are the U.S. & Mexico Cooperating?”Latin America Advisor. Available at https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/how-well-are-the-u-s-mexico-cooperating/

[67] Osborn, C. 2023. “Mexico Could Spoil New U.S.-China Fentanyl Plan.” Foreign Policy. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/17/apec-mexico-united-states-china-fentanyl-amlo-biden-xi/