The Congolese story is indeed tangled. Referring to the previous article on Security Outlines, titled “African mining industries: How a blessing becomes a curse”, the following text is looking at specific relationships between the most influential figures of the Congolese mining sector. To begin with, it will clarify the state´s disastrous condition and its path towards current status. Most importantly, this article introduces the main personals who stand behind the giant extracting and mining deals that are posing a major obstacle for the DRC to get out of the misery.

The DRC can hardly be called democratic, or even a republic

The very first democratic elections became reality in 2006, when a son of more than one decade ruling dictator Kabila replaced him. The presidential campaign of Kabila junior had been largely financed with a help from a diamond magnate Dan Gertler of Israeli origin. With these elections, the dream of a Congolese democracy disappeared as soon as it was dreamt about. The last data available from Transparency International Corruption Perception Index ranks this state 170/180 countries taken into consideration [1]. In the international policy arena, there is a common belief that if a nation loses its trust towards democratic elections, it already means a defeat of democracy [2]. As Marshall (2015) stresses: “Many authors agree on the fact that it is hard to name the DRC democratic, or even a republic (referring to Kabila´s ruling).” [7]

An exceptional book The Looting Machine written by Tom Burgis brings together stories, rare witnesses, interviews and clear background context from within such countries where wealth can disappear with a wave of a magic wand. This book is not only one of the main sources for the following text, but also a great piece for those who want to get deeper insight on issues of doubtable mining corporations elsewhere in Africa.

Who belongs to the elite group?

The beginnings of an exclusive class of actors date back to the time when president Laurent Kabila appointed Augustin Katumba, a capable trader with international experience, as the governor of Katanga. He did so on the recommendation of the Finance Minister Mwan Nang, leader of a rebel group at the same time. Back then, the president had to defend his country against the attacks directed from Rwanda. The weekly deliveries of at least 4 million USD from both public and private mining companies to the state treasury were significantly helpful in Kabila’s effort to consolidate his power. Mr. Katumba was the right type of person to gain dominance over the mining sector due to his intelligence and ability to get deeper into the structures of a state-owned mining company Gécamines. In a short time, Mr. Katumba became a part of president Kabila’s closest circle of advisors. After Kabila’s death, Mr. Katumba and the Finance Minister Mwan Nang were chosen to hold the government together because the presidential successor, Joseph Kabila Jr., was a military general with no experience in politics.

In 2002, United Nation’s investigators accused Mr. Katumba of being a key figure in an elite organized crime network of illegal mining and trafficking of Congolese minerals. UN expected this trade to gain 5 billion USD in selling state-owned raw materials to private companies over three years, without any sign of financial compensation directed to the state treasury. In order to avoid sanctions by the UN, Katumba was officially removed from the office. Nonetheless, thanks to his contacts he managed to build a “shadow state” and was able to manipulate elections and still serve as a patron of illegal businesses. Furthermore, president Joseph Kabila gave him his full confidence, so Katumba became untouchable. His “shadow state machinery” has been quietly functioning as an engine for the war policies and extraction frauds of the DRC supplied by foreign funds. Despite the fact that hostile ethnic groups are fighting in ongoing wars, they find the common ground in the matters of raw materials business, because: “War changes, but business goes on.“ [6]. In this way, Congolese militias made 185 million USD in 2008 from coltan and minerals, citing the need for funding during the war.

Katumba’s shadow state meets international corporations

Another key player in this elite group is Dan Gertler, an Israeli, known as the link between Katumba’s shadow state controlling minerals and international mining corporations. How has this person become the president’s confidant? Similar to the pathway of Joseph Kabila, Gertler began as a „vocation son“ and, as a descendant of an Israeli diamond magnate, went to Angola to search opportunities and experience. During one of many war crises, President Laurent Kabila’s army needed money to defend against the attacks directed from Uganda and Rwanda. With a monopoly on access to Congolese diamonds, Gertler brought President Kabila the 20 million USD he needed without delay. From trading with state-owned diamond companies (state-owned means in the hands of the president), Gertler shifted his focus to cobalt from Katanga Province. Its prices rose dramatically, mainly due to the Chinese market’s interest and specialization in electronic products to which cobalt is an essential component.

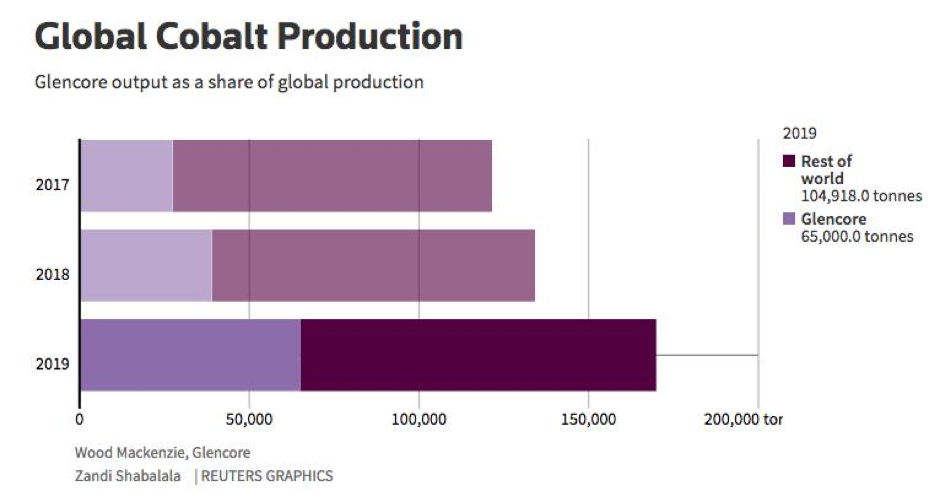

According to the latest information available, there are five large corporations in total operating in the DRC: Gécamines, Glencore, which has Fleurette Group revenue rights, China Molybdenum and Vale (whose 40 % of the revenue travel to China) [3]. Glencore is owned by no one else than Dan Gertler [4]. It follows that Congolese mineral wealth is divided equally between Chinese companies and Congolese Gécamines, and thus the profit goes either to China or into the shadow state machinery managed by the president´s closest fellows.

Guarantees based on the money from minerals

Thus, the Israeli with the owner of the Congolese Gécamines began to dictate not only the distribution of mining profits throughout the DRC, but also the trade relations with China. This relationship of the guarantees of political, trade and military power was based on Gertler’s money. A confidential report by a global risk analysis firm, as quoted by Foreign Policy magazine, would later describe Gertler’s philosophy as such: “everyone has a price and can be bought.” [5] Smooth deals and transactions were president’s utmost priorities. The strong shadow state is still a major obstacle for overcoming Congolese poverty, as voters starve and politicians buy their votes through the money from minerals. According to Kofi Annan’s Africa Progress Panel calculations, between 2010 and 2012, the DRC lost about 1.36 billion USD in business with Gertler’s international companies, which is more than it received through humanitarian aid during the same period [6].

Sources:

- Transparency International. (2020). Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo#

- Wolters, Stephanie. (2019). Slamming the door on democracy in the DRC. The Congolese chose change, but African and international responses to the election deprived them of it. issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://issafrica.org/iss-today/slamming-the-door-on-democracy-in-the-drc

- Kay, Amanda. (2018). 5 Top Cobalt-mining Companies. investingnews.com. Retrieved from https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/battery-metals-investing/cobalt-investing/top-cobalt-producing-companies/

- Doherty, Ben. (2017). Everything you need to know about Glencore, Dan Gertler and their interest in DRC. theguardian.com. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/nov/05/what-is-glencore-who-is-dan-gertler-drc-mining

- Blum, Petra., Langhans, Katrin., Obermaier, Frederik., Obermayer, Bastian., Zick Tobias., & Zihlmann, Oliver. (2017). The Broken Heart of Africa. projekte.sueddeutsche.de. Retrieved from https://projekte.sueddeutsche.de/paradisepapers/wirtschaft/mining-for-control-in-glencore-s-congo-e774511/

Printed sources:

- Burgis, Tom. 2015. The looting machine. Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers, and the Systematic Theft of Africa´s Wealth. London: HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 978-0-00-752310-8. 324 s.

- Marshall, Tim. (2015). V zajatí geografie. Bratislava: Premedia. ISBN 978-80-8159-513-4. 248 s.