Since the onset of the war in Ukraine, Russia has frequently used nuclear threats to influence Western decision-making by leveraging fear and uncertainty. However, nuclear weapons offer limited battlefield or strategic advantage for Russia while risking a decisive international response and consequently threatening Putin’s grip on power. Therefore, Russia’s potential nuclear strike cannot be considered a credible military action grounded in practical advantages or realistic outcomes.

Russia possesses one of the world’s largest nuclear arsenals. According to estimates from early 2024, its functional stockpile includes 4,380 warheads, of which around 1,710 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and heavy bombers, and 1,112 strategic and 1,558 nonstrategic warheads are held in reserve. An additional 1,200 retired but still largely intact warheads await dismantlement. [1] Thus, apart from the United States, no other country has a capability of nuclear destruction comparable to the Russian Federation.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin has been using its nuclear arsenal in an effort to steer Western policy towards its liking. [2] The first nuclear posturing came as early as February 27, 2022, mere days into the war, when Russian nuclear forces were put into a “special mode of combat duty”. [3] Nuclear threats were made throughout 2022 and peaked in October when coordinated Russian accusations of Ukraine preparing a “dirty bomb” coincided with nuclear military exercises and explicit nuclear threats to secure newly annexed Ukrainian territories. [2] In early 2023, Russia suspended its participation in the New START nuclear treaty with the United States, though did not withdraw from it. [4] Russia also made public its plans to station tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus. [5]

Most recently, in the fall of 2024, as Zelensky sought permission from Washington to use long-range missiles to strike targets inside Russia, the Kremlin announced that it would be amending its nuclear doctrine that had been adopted in 2020. [6] The amendment was approved on November 19, 2024, just days after the Biden administration reportedly authorised Ukraine to use the long-range missiles. The updated doctrine lowers the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons. It signalled that an attack with conventional arms that poses a “critical threat to sovereignty and (or) territorial integrity” of Russia or Belarus could warrant a nuclear response. [7] What constitutes a “critical” threat remains unclear, which is presumably the Kremlin’s intention to create strategic ambiguity. In contrast, the previous doctrine allowed the use of nuclear weapons against conventional threats only “when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy”. [8]

Why Russia Consistently Engages in Nuclear Threats

Russia’s deterrence ability has slowly been eroded throughout the war as the West crossed many of Russia’s so-called red lines with little to no repercussions. [9] Moscow may be using nuclear threats to reconstruct a credible deterrence posture by expressing a threat so severe that, even if unlikely, it cannot be disregarded. It is aimed not only at Western and Ukrainian policy-makers but also at the general population that is more susceptible to such warnings. Arguably, this tactic has achieved partial success, as despite unfulfilled threats and crossed red lines; it has severely slowed down Western decision-making out of fear of an escalation. [10] This delay has impacted Ukraine’s military capabilities, particularly in the early stages of the war, and continues to constrain operations today, notably through restrictions on using Western long-range missiles against targets inside Russia. [11]

Some have described Putin’s rhetoric as if he were pursuing the madman strategy. [12] The strategy, commonly associated with Richard Nixon’s foreign policy during the Vietnam War or with some aspects of Trump’s foreign policy, consists of convincing the adversary of one’s unpredictability. The idea is that the opposing side will not risk provoking the “madman” because it is unable to predict his or her reaction with any degree of certainty. [13] The Kremlin attempts to legitimise the notion through persistent nuclear threats and create uncertainty about its intentions.

How Russia Could Use Nuclear Weapons

Russia would likely consider the employment of nuclear weapons to force Ukraine into submission or negotiations and to divide its Western supporters. Such action would plausibly occur only in extreme circumstances, either facing an imminent military defeat [14] or needing to break a stalemate. [15] To that end, three to four possible uses come to mind. [16]

The first is the “escalate to de-escalate” approach. Russia might detonate one or several warheads to demonstrate resolve and force, but cause minimal casualties or damage – possibly a high-altitude detonation over the Black Sea or a test in Siberia. Such employment of nuclear weapons would simply be very extreme nuclear blackmail and could potentially divide to a degree some of Kyiv’s Western supporters, but it risks a serious response from not just major Western but also, importantly, non-Western actors. For Moscow, this strategy would be a serious gamble that could easily backfire, especially since both Ukraine and the West have been resisting Russian threats for a long time. [9] It thus could not be presumed that after a show of force like this, Washington or Brussels would simply give up on their support or that Ukraine would give in to Russian demands.

The second possible employment would be aimed at military targets using tactical nuclear weapons. However, it is difficult to determine where such a strike could be aimed to be worthwhile. Ukraine has been under aerial and missile attacks for over two years at this point, and its forces are spread out all across the front line and the interior. Launching a nuclear weapon against a dispersed force like Ukraine’s would thus be ineffective, as there is no concentration of forces that would present a clear target. [16] Therefore, Russia would most likely target stationary infrastructure or supply hubs, which, although causing problems for Ukraine, would not result in a collapse of the front line, and the impact of the attack could be mitigated.

Tactical nuclear strikes would prove more effective in larger numbers, but such attacks would present several complications. Besides even greater escalation risk, these include potential damage to Russian morale and the nuclear fallout affecting Russia and Belarus. [16] Additionally, according to a claim by the Institute for the Study of War from late 2022, Russia was at that time “almost certainly unable to operate on a nuclear battlefield” due to its “chaotic agglomeration of exhausted contract soldiers, hastily mobilised reservists, conscripts, and mercenaries”. [17] Given the intensity of combat and losses suffered in Ukraine throughout the war, one might question Russia’s current ability to exploit any advantages gained through potential nuclear strikes.

The third option would be a decapitation strike on Kyiv aimed at eliminating Ukrainian political and military leadership while destroying key infrastructure, disrupting communications and creating widespread chaos. Whilst a decapitation strike would prove devastating, such indiscriminate use of weapons of mass destruction against a mostly civilian target would spark a fierce reaction from the rest of the world, nullifying any operational advantage it might have initially achieved. This outcome would similarly arise from strikes against any other major civilian target. What is more, the destruction of civilian targets is not a reliable way to break enemy morale and could have the opposite effect on the Ukrainian population, galvanising its resolve. [16]

Chinese and Indian Perspective

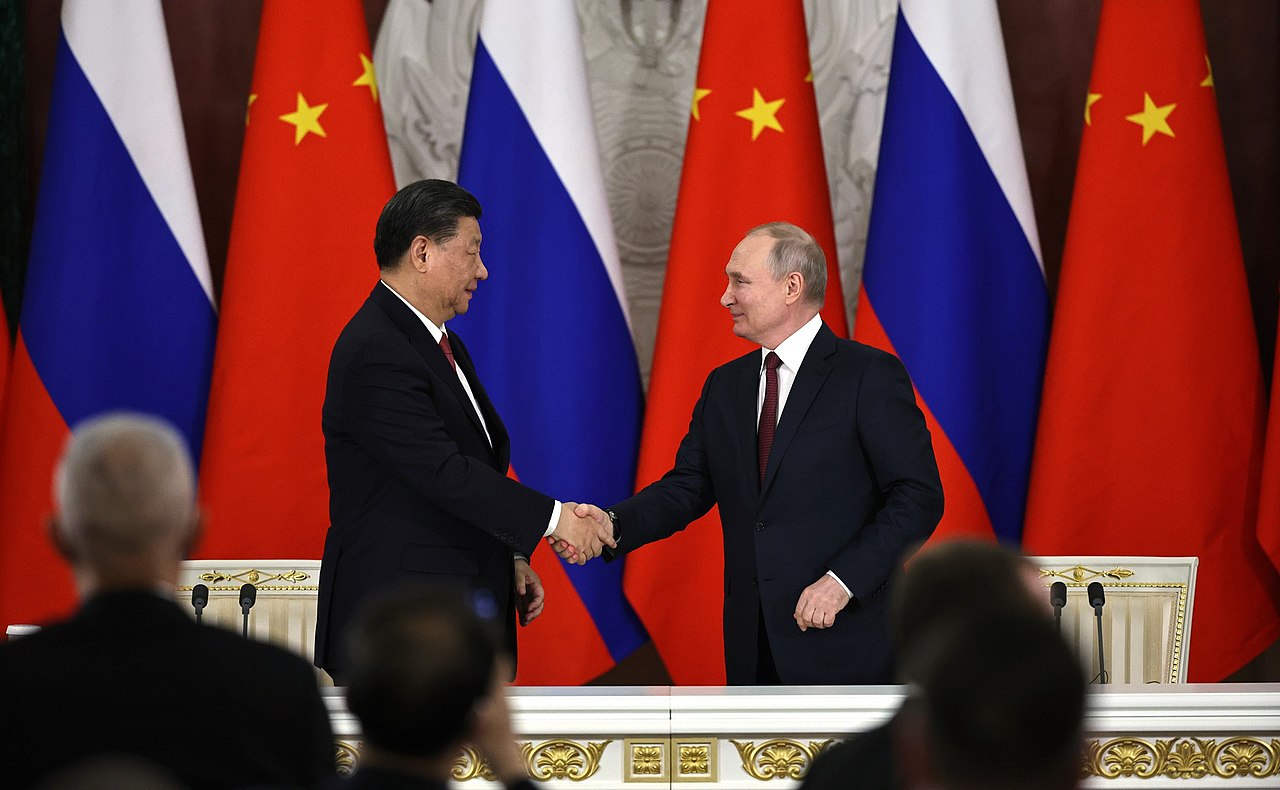

Since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of Western sanctions on Russia, Russia has become increasingly economically dependent on China [18] and India [19]. In fact, Russia’s ability to withstand Western sanctions has largely depended on this very reorientation. [20] Whether through trade in natural resources with both Asian nations or the import of dual-use goods from China, the Russian economy and, by extension, the war effort depend on these relationships.

But when Russian nuclear threats were at their peak in October 2022, both China and India, despite their cautious neutrality, came out and denounced Russian nuclear threats. Xi Jinping issued a warning to Putin that the international community should “jointly oppose the use of, or threats to use, nuclear weapons” and the world should “advocate that nuclear weapons cannot be used, a nuclear war cannot be waged, in order to prevent a nuclear crisis”. [21] India’s Defence Minister warned his Russian counterpart that neither side should use nuclear weapons and that “the prospect of the usage of nuclear or radiological weapons goes against the basic tenets of humanity”. [22] According to U.S. officials, it was these threats that helped deter Putin from using nuclear weapons. [23]

While China and India still cautiously maintain strategic neutrality in the conflict, a Russian nuclear strike would likely force them to reevaluate their positions. Both countries maintain a long-standing no-first-use nuclear doctrine, and as such, they would not support nuclear strikes against a non-nuclear state. Moreover, international outrage would possibly extend to developing nations, which might view a nuclear attack on a non-nuclear state as a dangerous precedent for themselves. These considerations place both India and China in uncomfortable positions, prompting them to go to great lengths to avoid being placed in such situations in the first place. [24]

Western Reaction

The range of possible Western reactions is limited, as many steps against Russia, especially those less radical, have already been taken. Nevertheless, the West would have an imperative to react – and to do so in unity. From the Western perspective, Putin must not gain anything from such a strike. Otherwise, a precedent would be set that nuclear attacks bring success. On the contrary, the response must ensure that Russia’s military position does not improve from such a strike and that its political and economic standing, including Putin’s own, significantly deteriorates as a result. [25]

The goal of Russian nuclear deterrence has been to deter any Western intervention and stop their support for Ukraine, [2] but the actual usage of nuclear weapons would likely lead to the opposite result. Western leaders have so far indeed consistently signalled certainty of retaliation while preserving ambiguity regarding the nature of the response. [2] U.S. President Joe Biden said the response would be “consequential” and that Russia would “become more of a pariah in the world than they ever have been. And depending on the extent of what they do will determine what response would occur.” [26] U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has emphasized that the American response would be “catastrophic” and that “in private channels we [the United States] have spelled out in greater detail exactly what that would mean.” [27] Despite the anticipated transition to a new Trump administration with a different foreign policy approach in January 2025, Russia cannot discount the probability of a serious American reaction to any nuclear attack.

Credibility of Russian Nuclear Threats

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte recently claimed that he does not see any imminent threat of nuclear weapons being used by Russia. Given the limited strategic value of a nuclear strike for Moscow and the associated risks, including a decisive Western response and the threat to relations with China and India, the cost-benefit calculation becomes straightforward. Russia stands to gain little from such an attack whilst risking both stiffer opposition and the potential loss of crucial economic partners.

Moreover, the Russian political system is built around Putin, who has been carefully centralising power for two and a half decades. [28] If Russia begins to lose or stall in Ukraine, it could threaten Putin’s regime. However, resorting to nuclear weapons might provoke an international backlash severe enough to ensure its downfall. Putin is thus incentivised not to authorise nuclear strikes, as the nuclear attack would likely pose an even greater risk to his position than battlefield setbacks. The scale and nature of the conflict in Ukraine would have to be completely and fundamentally altered in order to change this calculation in such a way that a nuclear strike would benefit him, which appears improbable in the foreseeable future.

While nuclear escalation remains a serious concern requiring careful attention, the actual likelihood of a Russian nuclear strike seems minimal, given the severe consequences for both Russia and Putin personally. The Kremlin’s nuclear blackmail, assuming rational and informed decision-making, likely represents political leverage rather than genuine intent, as has been demonstrated on numerous occasions in the past. [9]

Article reviewed by Jan Míček and Dávid Dinič

Sources

[1] Kristensen, H. M., Korda, M., Johns, E., & Knight, M. (2024). Russian nuclear weapons, 2024. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 80(2), 118–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2024.2314437

[2] Williams, H., Hartigan, K., MacKenzie, L., & Younis, R. (n.d.). Deter and divide: Russia’s nuclear rhetoric & escalation risks in Ukraine. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from https://features.csis.org/deter-and-divide-russia-nuclear-rhetoric

[3] Russland-Analysen: Chronik: 21. – 27. Februar 2022. (2022, March 8). Retrieved 31 October 2024, from Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung website: https://www.bpb.de/themen/europa/russland-analysen/nr-415/508979/chronik-21-27-februar-2022/

[4] Agence France Presse (AFP). (2023, February 21). Putin says Moscow suspending participation in new START nuclear treaty. Barron’s. Retrieved from https://www.barrons.com/news/putin-says-moscow-suspending-participation-in-new-start-nuclear-treaty-d307fa0f

[5] Chen, H., Humayun, H., Knight, M., Carey, A., Gigova, R., & Kostenko, M. (2023, March 26). Russia plans to station tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus, Putin says. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/25/world/russia-putin-nuclear-weapons-belarus-intl-hnk/index.html

[6] Williams, H. (2024). Why Russia is changing its nuclear doctrine now. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-russia-changing-its-nuclear-doctrine-now

[7] Ob utverzhdenii Osnov gosudarstvennoy politiki Rossiyskoy Federatsii v oblasti yadernogo sderzhivaniya [Об утверждении Основ государственной политики Российской Федерации в области ядерного сдерживания] [On the approval of the Basic principles of state policy of the Russian Federation in the field of nuclear deterrence]. (2024). Kremlin. Retrieved from http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/ru/KrzVeeTCkT05CCvgIoY03xuvIdkVslkx.pdf

[8] Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence. (2020). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/international_safety/1434131/

[9] Dickinson, P. (2024). Putin is becoming entangled in his own discredited red lines. Atlantic Council. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/putin-is-becoming-entangled-in-his-own-discredited-red-lines/

[10] Bielieskov, M. (2024). Time to make Russia worry about the West’s red lines in Ukraine. Atlantic Council. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/time-to-make-russia-worry-about-the-wests-red-lines-in-ukraine/

[11] Ukraine updates: Putin warns against long-range weapons use. (2024, October 27). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-updates-putin-warns-against-long-range-arms-use/live-70612184

[12] Abramsky, S. (2022, April 22). Daniel Ellsberg on the existential threat of global conflict. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/world/daniel-ellsberg-ukraine/

[13] McManus, R. W. (2019). Revisiting the madman theory: Evaluating the impact of different forms of perceived madness in coercive bargaining. Security Studies, 28(5), 976–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2019.1662482

[14] Gannon, J. Andrés. (2022). If Russia goes nuclear: Three scenarios for the Ukraine war. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/article/if-russia-goes-nuclear-three-scenarios-ukraine-war

[15] Giovannini, F. (2022). A hurting stalemate? The risks of nuclear weapon use in the Ukraine crisis. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved from https://thebulletin.org/2022/03/a-hurting-stalemate-the-risks-of-nuclear-weapon-use-in-the-ukraine-crisis/

[16] Alberque, W. (2020). Russia is unlikely to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine. International Institute for Strategic Studies. Retrieved from https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2022/10/russia-is-unlikely-to-use-nuclear-weapons-in-ukraine/

[17] Russian offensive campaign assessment, October 1. (2022, October 1). Retrieved 2 November 2024, from Institute for the Study of War website: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-1

[18] Kluge, J. (2024). Russia-China economic relations: Moscow’s road to economic dependence. SWP Research Paper. https://doi.org/10.18449/2024RP06

[19] Bajpaee, C., & Toremark, L. (2024). India–Russia relations. Chatham House. Retrieved from https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/10/india-russia-relations

[20] Feldstein, S., & Brauer, F. (2024). Why Russia has been so resilient to western export controls. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/03/why-russia-has-been-so-resilient-to-western-export-controls?lang=en

[21] Lau, S. (2022, November 4). China’s Xi warns Putin not to use nuclear arms in Ukraine. POLITICO. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/china-xi-jinping-warns-vladimir-putin-not-to-use-nuclear-arms-in-ukraine-olaf-scholz-germany-peace-talks/

[22] India’s defence minister warns against nuclear weapons in call with Russian counterpart. (2022, October 26). Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/indias-defence-minister-warns-against-nuclear-weapons-call-with-russian-2022-10-26/

[23] MacKenzie, L. (2024). Six days in October: Russia’s dirty bomb signaling and the return of nuclear crises. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/six-days-october-russias-dirty-bomb-signaling-and-return-nuclear-crises

[24] Scobell, A., Singh, V. J., & Stephenson, A. (2022). What a Russian nuclear escalation would mean for China and India. United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved from https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/11/what-russian-nuclear-escalation-would-mean-china-and-india

[25] Agence France Presse (AFP). (2022, September 24). What could happen if Putin used nuclear weapons in Ukraine? Radio France Internationale. Retrieved from https://www.rfi.fr/en/international-news/20220924-what-could-happen-if-putin-used-nuclear-weapons-in-ukraine

[26] Davies, A. (2022, September 17). Ukraine war: Biden warns Putin not to use tactical nuclear weapons. BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-62936643

[27] Smith, A. (2022, September 26). Russia faces ‘catastrophic’ consequences if it uses nuclear weapons, U.S. warns. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/russia-catastrophic-consequences-nuclear-weapons-ukraine-us-warns-rcna49365

[28] Graham, T. (2023). How firm is Vladimir Putin’s grip on power? Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/how-firm-vladimir-putins-grip-power