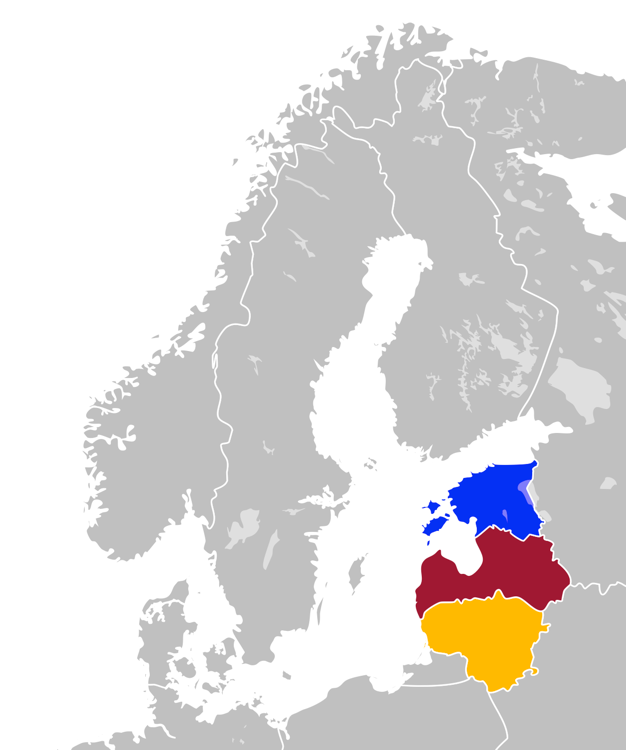

In Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security, Buzan and Weaver predicted that the Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – would be part of the West for most purposes, except for security issues. [1] This article aims at disproving their prediction that these states would not be part of the West regarding security. Today’s Baltic states are too deeply in the Euro-Atlantic structures and mentally far from the Russian Federation to be perceived as part of the post-Soviet region mainly because of their geographical position.

Using the Regional Security Complex Theory, the Near Abroad Policy of the Russian Federation (FR or Russia) and focusing on the 2007 cyber-attacks on Estonia, the aim is to demonstrate how relations of the Baltic states towards Russia (and vice versa) work and show the shift of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania from Russia towards the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), therefore becoming more part of the West than East.

As the milestone of the transition, this article marks the year 2007 when Estonia experienced a bilateral dispute with Russia concerning the relocation of the Bronze Soldier statue, a Soviet reminder of the liberation of Tallinn in 1944, followed by massive cyber-attacks which paralysed the country for almost three weeks.

Disclaimer: This article does not suggest that the Russian Federation orchestrated or got involved directly in the 2007 cyber-attacks on Estonia. The article accepts and follows that the incident has never been officially attributed to any state entity.

At the creation of the Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT), Buzan concluded that for a security complex to be created, elements of (1) existing security links between and among states, (2) patterns of amity or enmity, (3) power relations and (4) other links, such as geographical, political, strategic, historical, economic, or cultural must be present in the region. [2]

In general, a security complex is defined as a “group of states whose primary security concerns link together sufficiently closely that their national securities cannot realistically be considered apart from one another”. [2] All four elements seem to be achieved concerning the Baltic states and their relations with Russia. These countries have geographical proximity and solid and emotional historical ties, an overall complicated relationship with Russia, and a similar threat perception in which Russia plays a crucial role. Plus, the mere fact that we refer to them as the ‘Baltic states’ in international politics shows their connection.

According to Buzan, Russia-Baltic states create one of the four sub-complexes of a post-Soviet regional security complex. Besides the Baltic states, there is a sub-complex constructed of Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine; then Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia; and lastly, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Regional hegemon: saviour or predator

Estonia’s, Latvia’s, and Lithuania’s history, present, and future derive from Russia’s aspiration to become a hegemon – if not a global one, regional one at least. However, the Baltic states are part of the Euro-Atlantic structures, which “runs in conflict with Russia’s strive” to re-establish itself as a regional and global power. [3]

According to Ayoob, the hegemon’s legitimacy in the region is based on several factors. Besides the importance of military and technological capacity, providing collective good, military help, or political protection is also important. The tension appears if the countries in the region do not grant an aspiring hegemon this legitimacy.

Given the problematic historical experience of the Baltic states with Russia, granting it any power over their fate is not an option. Therefore, the mutual relations resemble what Ayoob describes as a state, in which an aspiring hegemon is not seen as a saviour but a “regional predator and the major threat” in the region. [4]

Such regions (sub-regions) are expected to be unstable and periodically in crisis. These occurrences are not too familiar to the Russia-Baltic states sub-complex, which probably has more to do with strong Euro-Atlantic security ties than stability in the sub-region.

Going back to Buzan, he acknowledges some states being ‘buffer zones’. Considering that the Baltic states are geographically close to Russia and since the 90s continuously fostered and cultivated their partnerships with the Euro-Atlantic structures, we can label them as a buffer zone of two geopolitical spaces – Russian and European/Western. Thus, it is no surprise that the Baltic states’ accession to the EU has been commented on as their “return to Europe and the West”. [5]

Modern roots of the troublesome relations

The historical experience Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have with Russia cannot be considered peaceful or untroubled. They were occupied by the Soviet Union since 1940 and had become part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1940 until September 6, 1991, when they gained independence. Moreover, this new era of three independent countries has raised another dispute with the RF.

According to Baltic states, independence was a restoration of their former pre-war statehood. Contrarily, Russia claims these states are new and obtained the Soviet Union’s consent to become independent.

Any continuation of previous statehood is refused by the RF, and Russia has repeatedly been using this issue to dispute the legal nature of the Baltic states’ statehood. [6] [7] For many years, Baltic states were put into the position of independent yet owing states that should be thankful to Russia for their existence.

To fully understand the picture of the post-Soviet sub-region, we also need to discuss Russia’s approach to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. In general, Russia follows the Near Abroad Policy, a concept introduced in 1993 after the collapse of the USSR. This foreign policy makes the RF responsible for ensuring the security and stability of its former territories and the Russian minority living in these territories.

The Russian minority is referred to as the ‘Russians Abroad’, and their motherland promises to ensure and protect them wherever they are. This basically means Russia is ready to come and help if its minority is “supposedly oppressed outside the borders of Russia”. [8] [9]

The Near Abroad Policy follows up on Russia’s hegemonic aspiration in the region and may be seen as a sign of strength. However, as Kakhishvili points out, the collapse of the USSR triggered an identity crisis for the former hegemon that found itself struggling to accept the new post-Cold war reality. [9] Therefore, the Near Abroad Policy can also be perceived as an endeavour to maintain already lost authority.

2007: Estonia‘s Bronze Year

Looking closely at the current states of relations Russia has with Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, there is one particular incident that has shaped the development of mutual perception – the Estonian “Bronze soldier Year” crisis in 2007, as is the event referred to in the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Yearbook. [6] This incident is mainly known for its cyber-attacks in which about one million computers took part, according to the Estonian former Minister of Defence. [10]

Even though the event has not been officially attributed to Russia, it has shaped Estonia’s security policy – and thus policies of Latvia and Lithuania – more than any other incident and led the Baltic states even deeper into the Euro-Atlantic partnership and far away from the Russian Federation.

The core of the incident lay in the dispute between Russia and Estonia concerning the relocation of the Bronze Soldier statue (during Soviet times called the “Monument of the Liberators of Tallinn”). The Estonian government aimed to move this statue because it was non-favourable by Estonian to whom it reminded the times under the Soviet Union.

On the contrary, the Russian government and the Russian minority living in Estonia opposed any relocation. The dispute led to protests supposedly driven by “false Russian news” (originating in Russia) about the statue and nearby Soviet graves being destroyed. [11] Thus, people were rioting in the capital city, Tallinn, and even sieged the Estonian Embassy in Moscow. [6]

Then, from April 27 to May 18, 2007, Estonia found itself under massive DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks. This attack technique “uses numerous systems to perform the attack simultaneously” and floods the targeted system with so many commands and requests that it becomes unavailable for all users. [12] The campaign took down the Estonian Internet and websites of Estonian Parliament, ministries, media, or banks had been unavailable. The country could not function properly, leaving its people uninformed and off-line.

Patriotic hackers acting on their own

As later confirmed by the Estonian government, the flood of commands mainly originated from Russian IP addresses, and online tutorials on how to become part of the attacks were written in the Russian language. [10] Moreover, Kremlin ignored any of Estonia’s appeals for help. [11] Following these clues, Estonia tried to denounce the RF for the attacks. However, no other substantive evidence to support such claims has been published, and Russia denies its involvement until today. [11] [13] [14]

The attack-launching individuals were concluded to be “patriotic hackers” who acted “defending the interests of their state”. [15] Despite the non-existing attribution, Liik concludes that 2007 introduced a “new low” to bilateral relations with the RF. [6]

On the other hand, Estonia turned this experience into its benefits. It introduced “cybercrime” as a criminal offence, passed its first Cyber Security Strategy and, in cooperation with NATO, founded the Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE). [16]

The Estonian experience was also a “wake-up call” for NATO and it triggered the alliance’s cyber-oriented activities. [17] In 2008, it has been approved NATO’s first Policy on Cyber Defence. In 2010, NATO adopted a new Strategic Concept that included the cyber agenda for the first time. From this year on, cyber is a full-fledged part of NATO’s agendas, becoming later a part of its collective defence core task (if interested in the topic, please see this article written by the same author).

Since their independence and further integration into NATO and the EU, Russia has been continuously losing its leverage over the Baltic countries. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are deeply integrated into the Euro-Atlantic structures today, thus politically and culturally drifting away from the Russian influence. Consequently, even the RF does not perceive them as part of the post-Soviet space but as a “Northern Europe”. [18] [19]

This drifting had obviously started before the 2007 cyber-attacks; however, Russia’s unwillingness to help with the investigation along with the mentioned clues (IP addresses originating from Russia, tutorials in Russian language and fake news spreading from – if not by – Russia) antagonised the Baltic states and the RF even more. The drifting accelerated a year later during the war in Georgia and escalated in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea. [18]

As a result of the annexation, Baltic states responded by a fast modernisation of their armed forces and increased an effort to meet the two per cent NATO military budget target. [20] Naturally, they are in a different position than Ukraine was in 2014. Based on the Trans-Atlantic relations, they possess the ability to pursue strategic deterrence (the ability to discourage or restrain an actor from taking an unwanted action), unlike Ukraine, which held no such capacity.

Despite this, are there ways Russia can put pressure on the Baltic countries to manipulate their behaviour on the international field? A potential move might be through their dependence on Russian natural gas. Before 2014, the rate of imported natural gas from Russia has been 100 per cent; since then, the Baltic states have put considerable efforts to integrate into the European energy network gas market. Nevertheless, the strong ties from the energy security perspective are here. A similar pattern can be identified in economic security: Russia remains the first trading partner to Lithuania, the second to Estonia, and the fourth to Latvia. [18]

Naturally, the RF would benefit from the control over the Baltic sub-region and could strengthen its position as an aspiring hegemon in the post-Soviet security complex. Despite the aspiration, however, the risks of crossing NATO and invoking a conflict with the Alliance are greater than the potential (and uncertain) gains (at least we still hope so, despite the events of the last month). [19]

We can probably expect the relations in the Baltic sub-region towards Russia to continue to be tense yet not escalating, while Russia will continue to focus elsewhere, especially now, having its hands full with Ukraine.

Sources:

[1] Buzan, Barry and Waever, Ole. 2003. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Buzan, Barry. 1991. People, States and Fears. An agenda for international security studies in the post-cold war era. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

[3] Andžāns, Māris. 2014. “Securitisation in Defining Regional Security Complexes: The Case of the Baltic States (2004-2013),” PhD thesis, Riga Stradins University. Online.

[4] Ayoob, Mohammad. 1999. From Regional System to regional society: exploring key variables in the construction of regional order. Australian Journal of International Affairs 53(3), 247-260.

[5] Lamoreaux, Jeremy W. and Galbreath, David J. 2008. The Baltic States as ‘Small States’: Negotiating the ‘East’ by Engaging the ‘West’. Journal of Baltic Studies, 39(1), 1-14.

[6] Liik, Kadri. 2010. “The ‘Bronze Year’ of Estonia-Russia relations.” In: Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Yearbook. Online.

[7] Fernandes, Sandra and Correia, Daniel. 2018. (Re)securitisation in Europe: the Baltic States and Russia. Debater a Europa 18, 103-129.

[8] Safire, Williams. 1994. “On language: The Near Abroad.” The New York Times. May 22, 1994. Online.

[9] Kakhishvili, Levan. 2013. Accessing Russia’s Policy Towards its ‘Near Abroad’. E-International Relations. June 17, 2013. Online.

[10] Blomfield, Adrian. 2007. “Russia accused over Estonian ‘cyber-terrorism’.” The Telegraph. May 17, 2007. Online.

[11] McGuinness, Damien. 2017. How a cyber attack transformed Estonia. BBC.com. April 27, 2017. Online.

[12] National Initiative For Cybersecurity Carrers and Studies (NICCS). n.d. “Cybersecurity Glossary: distributed denial of service.“ Accessed October 31, 2021. Online.

[13] Council on Foreign Relations. 2007. Estonian Denial of service incident. Last modified May 2007. Online.

[14] Cottey, Andrew. 2013. Security in the 21st Century Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[15] Dong, Yao. 2019. The Jus Ad Bellum in Cyberspace: Where Are We Now and What Next? New Zealand Journal of Public and International Law 17(1), 41-66.

[16] Sierzputowski, Bartłomiej. 2019. The Data Embassy under Public International Law. International and Comparative Law Quarterly 68(1), 225-242.

[17] Rojčík, Ondřej. 2019. “Achievements and Failures of NATO Cyber Policies“. In NATO at 70: Outline of the Alliance Today and Tommorow, edited by R. Ondrejcsák, T. H. Lippert, 179-192. Bratislava: STRATPOL.

[18] Bergmane, Una. 2020. Fading Russian Influence in the Baltic States. Orbis 64(3), 479-488.

[19] Gorenburg, Dmitry. 2019. Russian Strategic Culture in a Baltic Crisis. George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, March 2019. Online.

[20] La Torre, Ilaria. 2019. The Baltic’s response to Russia’s Threat: How Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania reacted to the recent actions of the Russian Federation. FINABEL. European Army Interoperability Center, March 2019. Online.