Nigeria is a West African country with immense potential, and numerous experts predict that its significance will only grow in the coming decades. Still, it stands mostly in the shadow of contemporary events in other parts of the Sahel region. This lack of recognition seems unjustified. Nigeria not only boasts the largest economy on the continent but also possesses one of the strongest militaries and is the most populous country in Africa. What are the factors that support Nigeria’s future claim for hegemony? And what are the significant challenges that the country is currently facing?

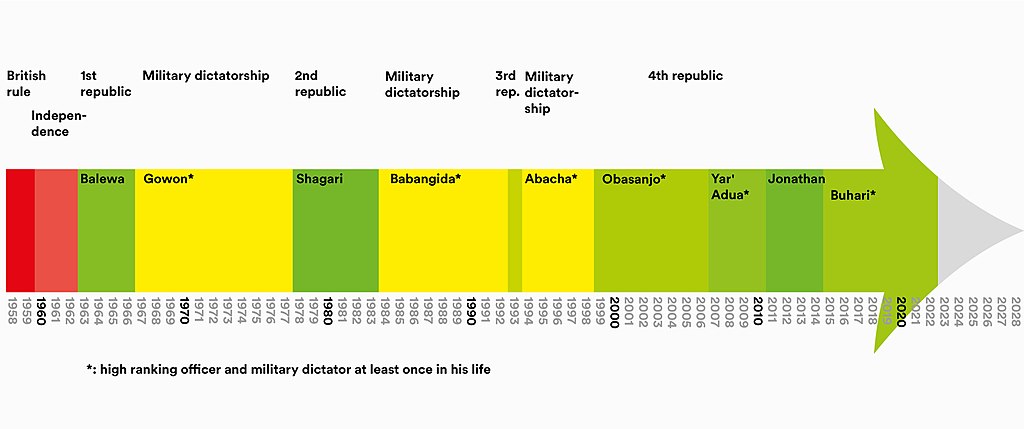

A short introduction, before we dive further into the analysis – Nigeria is partly a Sahelian country (it reaches into the Sahel in its northern parts) and is strongly affected by the spread of Islamic radicalism. It is a former British colony surrounded by a multitude of former francophone colonies like Niger, Benin, Cameroon, and Chad. Nigeria’s population is extremely heterogeneous, comprising of many cultures and hundreds of languages. Its population is, in fact, the largest one in Africa, reaching over 222 million people. The history of modern Nigeria started in 1914 when the colonial administration joined the protectorates of Northern and Southern Nigeria. The country gained its independence from the UK on October 1, 1960 [1], during the African „Wind of Change,“ as coined by the British PM Harold Macmillan earlier that year. [2]

Robustness of the Nigerian Market and Military Capabilities

Based on nominal GDP, Nigeria is the largest economy in Africa accumulating $504 billion. It is widely considered an emerging economy with immense potential for the future. It is a founding member of the African Union, a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the Commonwealth of Nations, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. [3]

In terms of trade, Nigeria stands out as a reliable partner, particularly when compared to its neighbouring countries. It boasts a commendable level of institutional and social stability, high foreign exchange reserves, and a stable exchange rate. The majority of its trade is conducted with EU countries – 30 % of Nigeria’s export flows to the EU, and 23 % of imported goods have European origin. Other significant trade partners include India (export) and China (import). [4]

Nigeria possesses abundant natural and human resources, with oil being the most prominent among them. Each day, approximately $100 million worth of oil is extracted from the ground. Nonetheless, these resources do not benefit most of the Nigerian population. It is estimated that 80% of oil revenues have enriched only 1% of the population. The country heavily relies on oil as its primary export commodity and government revenues, accounting for 97 % of the country’s export value. [5] Such overreliance on a single natural resource causes underdevelopment in other sectors of a country’s economy specifically in manufacturing, agriculture, or services, and is widely known as the „Dutch disease“. [6] However, the core of the issue is not the dependency on a single export commodity per se, but on the export of crude oil, which is to be refined elsewhere, resulting in a loss of a certain amount of profit. Ironically, Nigeria’s largest import is oil in its refined form. [7]

Besides being the largest economy on the African continent, Nigeria is also a contestant for a number one African country in terms of military spending, rivalling South Africa for primacy. [8] Nigeria has demonstrated the capabilities of its armed forces in numerous engagements (e.g. interventions in Sierra Leone and Liberia [9]), showcasing its unwavering interest in African affairs. In fact, 98.8 % of Nigeria’s peacekeeping forces were deployed within Africa, and between 1990 and 2018 they accounted for approximately 13 % of the total African peacekeeping troops. [8] Furthermore, Nigeria contributed around 54 % of military spending in West Africa between 2008 and 2017. [8] All these facts seemingly point out Nigeria’s formidable military power in the region.

Power in Multilateralism

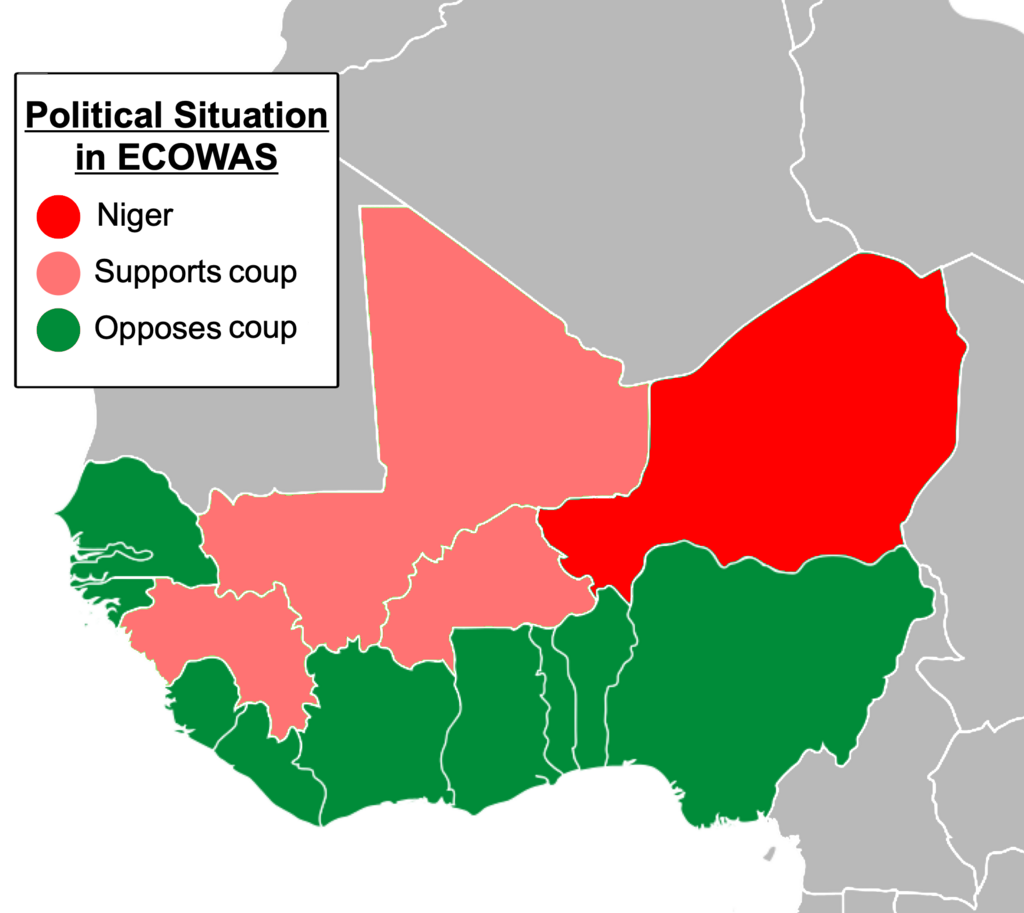

Nigeria is part of ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States), a regional bloc consisting of 15 member states. ECOWAS aims to foster cooperation and integration, ultimately leading to the establishment of a West African economic union. [10] During the 1990s, economic cooperation spilt over into the developmental and military sectors. This was given primarily by the prevalence of intrastate conflicts. Nigerian forces spearheaded most operations under the ECOWAS military wing ECOMOG, enabling the country to exert its influence over the political leadership in these states. Consequently, Nigeria assumed a dominant role within the organization. [11]

Despite several ECOWAS successes in regional cooperation, the organization still suffers from multiple limitations. A significant issue is, for example, the division between francophone and anglophone countries within the organization, especially when it comes to the issue of military interventions – francophone countries in the region tend to dismiss military interventions as a solution for regional issues. In fact, many French-speaking countries opposed the ECOMOG intervention in Sierra Leone in 1997. These countries preferred diplomatic solutions and viewed violence only as a last resort. Burkina Faso, for instance, opposed any form of military intervention in both Liberia and Sierra Leone. [9] Some of the francophone countries of the region even resort to labelling Nigeria as a regional bully. [12]

Obstacles to Overcome

Corruption stands out as one of the most pressing issues in the country today. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index reveals that Nigeria scores 24 out of 100 points. This places the country at a dismal 150th position out of the 180 countries surveyed, even trailing behind notoriously corrupt and institutionally weak states like Russia and Liberia. Even more concerning is that Nigeria’s corruption score has been steadily declining since 2016. [13] [14] Although the Fragile States Index shows that the conditions have been steadily improving in the last years, it still puts Nigeria in the 15th rank of 179 observed countries. The state legitimacy criteria including corruption are among those that have been worsening lately. [15]

Practice What You Preach

Perhaps ironically, Nigeria acts as an arbiter of good governance, human rights, and democratic principles in the region, while notably suffering from insufficiencies in those areas.

Nigeria’s 2023 general elections serve as a good example of the favourable appeal but conflicted reality. In theory, the elections were democratic and competitive. However, numerous observers criticised them for being untransparent and flawed. This led to the lowest voter turnout since the end of junta rule in 1999. [16] [17] [18]Logistics challenges, malpractices, malfunctions of voting devices and violence in some parts of the country caused a significant setback for the elections. [17]

Furthermore, while fighting the terrorist groups on Nigeria’s territory, the country’s elites often apply the collective punishment principle, which leads to severe human rights violations. Practices of Nigeria’s Armed Forces include unlawful detainment, torture and even murder. [19] Officials deny any claims of such actions, contradicting human rights organisations such as Amnesty International. According to its report, at least 42 journalists were detained, threatened or harassed by security forces or otherwise denied monitoring of the event, during the 2023’s general elections. [20] [21] National Human Rights Commission stated, that there were 450 instances of human rights abuses and violations during the same elections. [21]

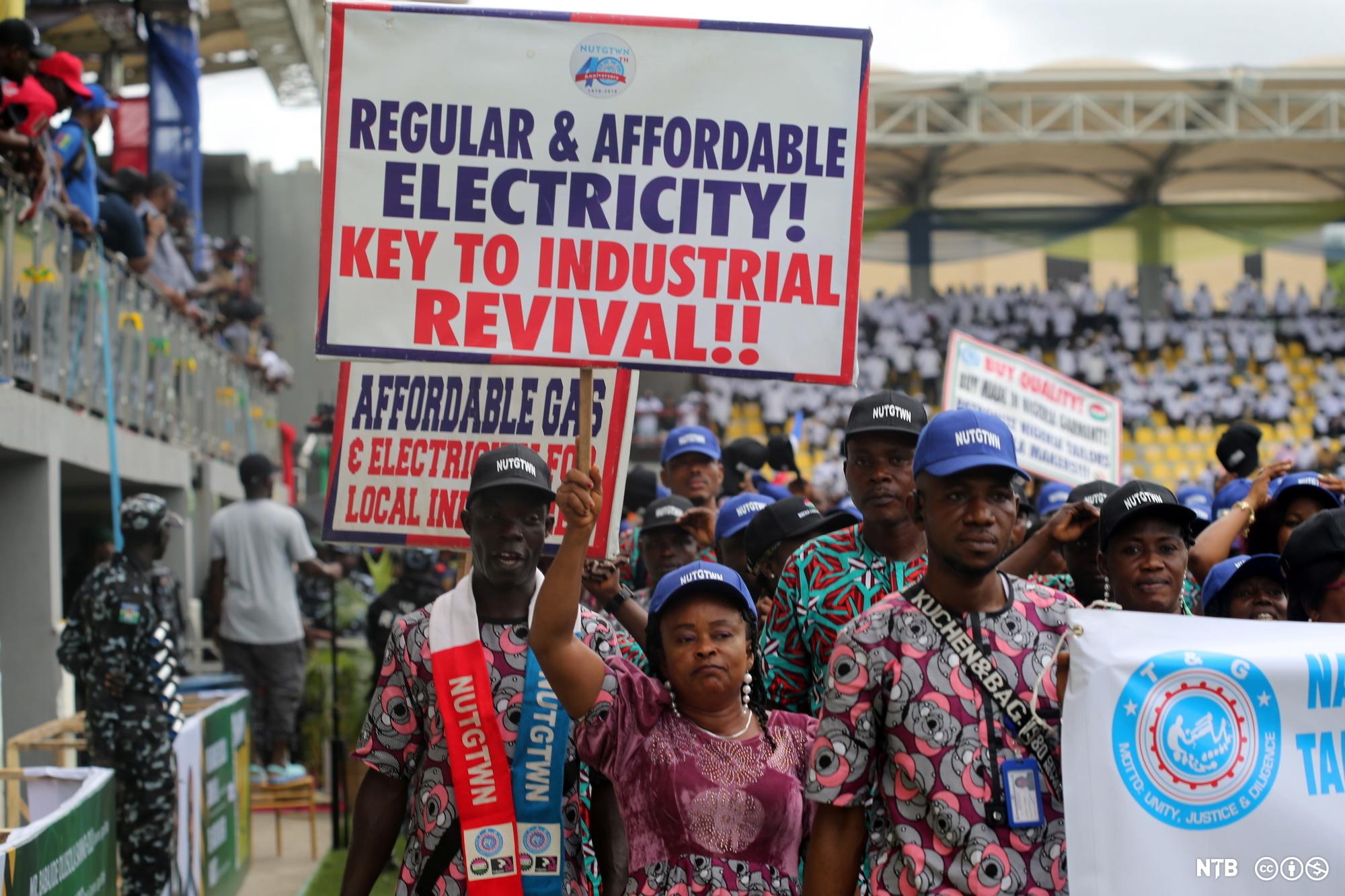

Another pressing issue is Nigerian infrastructure and access to electricity, which affects almost 40 % of the Nigerian population – according to 2017 data, only 60 % of Nigerians had access to electrical power. [24]Nigeria’s grid in 2022 could transfer circa 8,1 MW, whereas the peak demand was 19,8 MW and generating capacity allowed for up to 13 MW. [25] The government aims to solve the problem by diversifying its energy mix with additional nuclear power. In 2017, it signed a deal with the Russian state-owned company Rosatom to build two nuclear power facilities. [26] [27] However, the underdeveloped distributional network remains a critical bottleneck and the paramount reason for limited access to electrical power. [25] It is important to note that lack of access to electricity poorly affects not only the proper execution of public services but also contributes to tensions and stratification within the society.

Nigeria’s Islamic Terrorism Struggle

Given the amount of heterogeneity combined with the poor social and economic conditions for Nigerian citizens, the country is prone to religious extremism and associated terrorism.

According to the data from 2023’s Global Terrorism Index, Nigeria ranked 8th country most affected by terrorism. Out of the 20 worst terrorist attacks in 2022, three took place in Nigeria. ISWAP (Islamic State – West Africa Province) is responsible for the deadliest one from May 2022 in Borno state province, where 50 civilians were killed for a suspected provision of information to the ISWAP itself ranks 6th among the 10 most deadly terror groups of 2022 worldwide. Other Nigerian groups that made the list include Boko Haram (ranked 7th), and Indigenous People of Biafra (ranked 10th). [28] The first two are jihadist groups operating in the north of the country and seeking to establish a caliphate system, governed by sharia law. [28] [29]

From 2014 to 2021, Boko Haram alone has been responsible for more than 20,000 deaths and displacement of more than 2,1 million people, which besides direct humanitarian impacts, severely damages the country’s economic performance and well-being of its citizens, resulting in an endless spiral. [30] One of the most publicly known cases of acts of terrorism conducted by Boko Haram was the 2014 abduction of 276 schoolgirls in Chibok, located in northeast Nigeria. Only several of the girls were released or managed to escape, while others were raped, killed or forced into marriages. It is estimated that to this day, 98 Chibok girls remain in captivity.

But this incident is not mentioned only for its global outreach. It shows another crucial aspect of Nigeria’s obstacle on its way to regional hegemony – the lack of accountability of Nigerian elites. President Goodluck Jonathan attempted to downplay the abductions, viewing the news as a ploy by his opponents to undermine his credibility ahead of the 2015 general election. [29] According to Amnesty International, the Nigerian government has not led a single credible investigation into the gaps in security measures that lead to such events and harm the civilian population. [31]

As mentioned earlier, the government often applies collective punishment methods in the fight against terrorist groups and their members. Young men suspected of aiding or having joined Boko Haram are detained in the streets or taken from their homes. This practice has become a daily occurrence in the northeastern regions of the country. [19] These prisoners often never stand trial and are kept in “grim military facilities”, claims Amnesty International. [32] Such an approach only deepens the frustration of Nigerian society and distrust of its government officials.

Relative Deprivation and Tensions Within the Society

The prevalence of Islamic terrorism can be attributed, as stated above, to the issue of poverty. Building upon the theory of relative deprivation, it becomes evident that the most severe forms of collective violence tend to emerge from socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. In the case of Nigeria, this disparity is particularly notable in the north, where poverty rates reach up to 70 %, according to the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics. Furthermore, the region grapples with higher levels of illiteracy and youth unemployment.

The challenges faced by the population in this area are further worsened by the adverse effects of climate change, including drought and desertification. Consequently, many individuals who relied on agriculture, as a main source for their livelihoods, have been compelled to seek alternative means of earning money. Moreover, there is a strong sentiment in the northeast that the region is being economically neglected within Nigeria’s federal system. This criticism stems primarily from the government’s failure to invest in adequate infrastructure in this forested region. [22] [29] [30] Insufficient funding also plagues education. Data from UNICEF shows that one teacher is supposed to provide education to 100 pupils. [19] With Nigeria ranking lowest in the world for life expectancy at birth, standing at a mere 53 years according to the World Bank, the harsh realities of living conditions become starkly evident. [23]

However, it is fair to say that the impact of terrorism in the country seems to have decreased lately. Deaths and especially the number of attacks in 2022 fell considerably compared to 2021. [28]

Pivot to Domestic Policy as a Solution

A theoretical approach to possible solutions seems quite obvious – the Nigerian government should shift its focus inward, rather than outward. Politicians ought to strive to establish resilient institutions that deter corruption and ensure accountability. Nigeria must confront its historical legacy and work towards fostering a culture of integrity and responsibility, however difficult it may seem, especially if aspiring to become a regional (or even continental) leader.

Nigeria cannot achieve Pax-Nigeriana on the international front without stability at home. The superficial image it projects as a regional power is quite transparent. Nigeria suffers from significant deficiencies in physical, societal, and economic security. It excessively relies on a single source of income and fails to reinvest petrodollars into the economy. While the economy remains the country’s apparent strength, fundamental changes in its management are necessary for sustained growth.

The country desperately needs to provide some economic certainty and curb poverty. To disincentivise young men from resorting to criminal organisations such as Boko Haram or ISWAP, it is necessary to deal with decreasing youth unemployment and avoiding collective punishment measures. Development means security and vice versa. [14]

Article reviewed by Stanislav Šturdík and Veronika Zwiefelhofer Čáslavová

Sources

[1] Udo, R. K., Ajayi, J. F. A., Kirk-Greene, A. H. M., & Falola, T. O. (2023, October 30). Nigeria. Retrieved 1 November 2023, from Britannica website: https://www.britannica.com/place/Nigeria

[2] Macmillan, H. (1960, February 3). 1960: Macmillan speaks of ‘wind of change’ in Africa. BBC. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/3/newsid_2714000/2714525.stm

[3] Šerić, M. (2023, March 9). Nigeria: The Political And Economic Superpower Of The Future – Analysis. Retrieved 2 December 2023, from Eurasia Review website: https://www.eurasiareview.com/09032023-nigeria-the-political-and-economic-superpower-of-the-future-analysis/

[4] Coface. (2023). Nigeria: Country File, Economic Risk Analysis. Retrieved 2 December 2023, from Coface website: https://www.coface.com/news-economy-and-insights/business-risk-dashboard/country-risk-files/nigeria

[5] Hill, S. (2020, January 15). Black China: Africa’s First Superpower Is Coming Sooner Than You Think. Retrieved 27 November 2023, from Newsweek website: https://www.newsweek.com/2020/01/31/nigeria-next-superpower-1481949.html

[6] Ianchovichina, E., & Onder, H. (2017, October 31). Dutch disease: An economic illness easy to catch, difficult to cure. Retrieved 16 December 2023, from Brookings website: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/dutch-disease-an-economic-illness-easy-to-catch-difficult-to-cure/

[7] OEC. (2021). Nigeria (NGA) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners. Retrieved 2 December 2023, from The Observatory of Economic Complexity website: https://oec.world/en

[8] Aleyomi, M. B. (2022). Major Constraints for Regional Hegemony: Nigeria and South Africa in Perspective. Insight on Africa, 14(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/09750878211049485

[9] Dumbuya, P. A. (2008). Ecowas Military Intervention in Sierra Leone: Anglophone-Francophone Bipolarity or Multipolarity? Journal of Third World Studies, 25(2), 83–102. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/45194480

[10] ECOWAS. (n.d.). About ECOWAS | Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Retrieved 8 November 2023, from https://ecowas.int/about-ecowas/

[11] Cabada, L., Šanc, D., Bahenský, F., Ježková, M., Jurek, P., Krčálová, Z., … Ponížilová, M. (2011). Panregiony ve 21. století: vývoj a perspektivy mezinárodních makroregionů. Plzeň: Čeněk.

[12] Ogunnubi, O., & Okeke-Uzodike, U. (2016). Can Nigeria be Africa’s hegemon? African Security Review, 25(2), 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2016.1147473

[13] Transparency International. (2023, January 31). 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index. Retrieved 28 November 2023, from Transparency.org website: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022

[14] Yagboyaju, D. A. (2022). Nigeria: The Imperatives Of Internal Security And Development – Problems And Prospects. Conflict Studies Quarterly, (40), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.24193/csq.40.4

[15] Fragile States Index. (2023). Nigeria | Country Dashboard | Fragile States Index. Retrieved 18 February 2024, from Fragile States Index website: https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/

[16] Al Jazeera. (2023, June 29). Nigeria’s 2023 election eroded voters’ trust: EU observers. Retrieved 17 February 2024, from Al Jazeera website: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/29/nigerias-2023-election-eroded-voters-trust-eu-observers

[17] Times, P. (2023, March 13). EDITORIAL: The highs and lows of Nigeria’s 2023 presidential election. Retrieved 17 February 2024, from Premium Times Nigeria website: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/opinion/editorial/587427-editorial-the-highs-and-lows-of-nigerias-2023-presidential-election.html

[18] Oshewolo, S., & Ademola, A. (2023, August 1). Opinion: Nigeria and the flawed 2023 elections. Retrieved 17 February 2024, from The Round Table website: https://www.commonwealthroundtable.co.uk/commonwealth/africa/nigeria/opinion-nigeria-and-the-flawed-2023-elections/

[19] Knoechelmann, M. (2014). Why the Nigerian Counter-Terrorism policy toward Boko Haram has failed: A cause and effect relationship. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). Retrieved from International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) website: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep09448

[20] Ejekwonyilo, A. (2023, November 29). Amnesty International decries Tinubu’s failure to uphold human rights in Nigeria. Retrieved 17 February 2024, from Premium Times Nigeria website: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/647474-amnesty-international-decries-tinubus-failure-to-uphold-human-rights-in-nigeria.html

[21] Amnesty International. (2023, November 15). Nigeria: Human rights agenda 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2024, from Amnesty International website: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr44/7157/2023/en/

[22] Omaamaka, O. P., & Groupson-Paul, O. (2015). Nigeria’s Hegemony in West Africa – Counting the Cost. Journal International Studies, 11. https://doi.org/10.32890/jis2015.11.5

[23] The World Bank. (2021). Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Nigeria. Retrieved 2 December 2023, from World Bank Open Data website: https://data.worldbank.org

[24] Bello, O. (2017, September 11). Nigeria can become Africa’s first global superpower. Retrieved 1 December 2023, from Businessday NG website: https://businessday.ng/energy/power/article/nigeria-can-become-africas-first-global-superpower/

[25] Agusto & Co. (2023). 2023 The Nigerian Independent Electric Power Producers. Retrieved 12 January 2024, from Agusto & Co Store website: https://www.agustoresearch.com/report/2023-the-nigerian-independent-electric-power-producers/

[26] Nigeria moving ahead on nuclear power plant plan : New Nuclear – World Nuclear News. (n.d.). Retrieved 18 February 2024, from https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Nigeria-moving-ahead-on%C2%A0nuclear-power-plant-plan

[27] BBC. (2017, October 31). Russia to build nuclear power plants in Nigeria. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-41818933

[28] Institute for Economics & Peace. (2023). Global Terrorism Index 2023: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Retrieved from http://visionofhumanity.org/resources

[29] Akinola, O. (2015). Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria: Between Islamic Fundamentalism, Politics, and Poverty. African Security, 8(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2015.998539

[30] Okoli, A. C., & Lenshie, N. E. (2022). ‘Beyond military might’: Boko Haram and the asymmetries of counter-insurgency in Nigeria. Security Journal, 35(3), 676–693. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-021-00295-1

[31] Amnesty International. (2023, April 13). Nigeria: Nine years after Chibok girls’ abducted, authorities failing to protect children. Retrieved 28 November 2023, from Amnesty International website: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/04/nine-years-after-chibok-girls-abducted/

[32] Amnesty International. (2021, November 25). Nigeria: Mass prisoner release from unlawful military detention is testament to campaign power of ‘Knifar Women’. Retrieved 18 February 2024, from Amnesty International website: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/11/nigeria-mass-prisoner-release-from-unlawful-military-detention-is-testament-to-campaign-power-of-knifar-women/