Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to influence many aspects of human activity and the functioning of society, including the fusion of AI applications and security. In this context, we can identify two fundamental dimensions. The first dimension addresses how the existence and implementation of technology may threaten the security of individuals, states, and societal order and its stability. The intention of this approach is not to fuel the idea of „killer robots“ subjugating humanity, however, there is a logical link between this approach and the discussion of how the existence of AI can affect security. The second dimension is more straightforward, focusing on the link between technology and security. It deals with issues such as the dual-use potential of the technology, the possibility of its militarization, and the threat of its misuse. In other words, this dimension perceives AI technology as a tool rather than anything else. Both approaches are crucial to the debate and will therefore be discussed further in the following chapters.

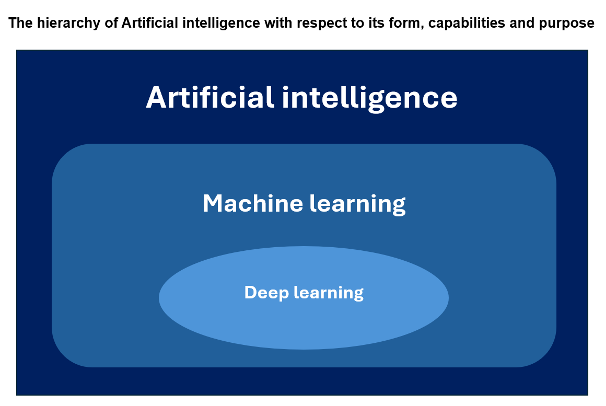

Current AI is primarily limited to the level of „Narrow AI“. It is used in various systems where AI replicates human behavior while augmenting it with computational power that surpasses human capabilities. Such systems are highly effective in solving specific tasks, which means they do not, by default, pose an imminent threat, as their abilities are bounded by design. [3] Still, there is no reliable way to rule out the possibility of AI reaching a point of singularity, where it could match or even surpass human intelligence while being fully aware of the surrounding environment and understanding the context of its actions. The main obstacle is achieving self-awareness. Making a well-grounded estimation of the degree of self-awareness can be highly problematic, as for now, it is unclear how to quantify and thus measure the degree of self-awareness reliably. [2] It is nearly impossible to unequivocally say how far we are from creating self-aware AI. Some experts in the field of artificial intelligence believe that the ability of AI to perceive its environment is inevitable and could become a reality within the next 10-20 years. [2] Moreover, some even believe we may have already surpassed this point in AI evolution. However, this debate is often greatly influenced by the already-mentioned challenging quantification of the phenomenon. In any case, the problem raises the question of what the security implications will be and what impact this situation might have on the functioning of society.

Following the previous article on Europe and AI, the question is how the application of advanced AI may threaten European citizens as individuals, European nation-states, and the EU as a political entity. These three protected actors are united by one crucial principle: the Rule of Law. [4] For clarification, we can perceive the Rule of Law as „a necessary foundation of any democratic, free, and open society.“ [5] The security of these referential objects derives from this societal setting, but applying advanced AI may collide with this principle. A particular legal-logical dilemma arises when AI systems become homogeneous or fundamentally close to human qualities. The problem is that from nature, „AI is not subject to the same normative restrictions, which the members of society are subjected to,“ and, as a result, „while not being limited by time and space, AI can shape any given reality, being prepared and programmed for it.“ [6] Therefore, if such advanced AI systems were to become an integral part of, for example, the legislative and executive process, it could latently affect the capacity of the EU or nation-states to provide an environment in which the rule of law is applied to all citizens equally.

The potential threat lies primarily in the already mentioned inability to limit AI in space and time while simultaneously not being dependent on any normative restrictions of society. The restrictions for AI come from its code, and developers often face the question of how exactly their AI system works. The truth is that, in many cases, the creators themselves are not sure how their system operates or whether it may evolve spontaneously in the future. Of course, this operational autonomy is the essence of AI’s functioning. However, in the frame of this autonomy, we cannot rule out the possibility that the AI may decide to rewrite its code. [7] This scenario is only possible if AI systems are equipped with the necessary capabilities, meaning that AI’s design enables it to rewrite its code while simultaneously allowing the AI system to do so. While the risk of this happening is not skyrocketing high, neither it is non-existent.

It is important to note that although it is possible to regulate the development and application of AI, AI itself cannot be regulated as such, primarily because it does not adhere to social norms. Moreover, not only can AI not be regulated like other technologies, but it has the potential to act as a regulator itself, influencing the regulation of individuals and general institutional regulation [5]. Evidence of this trend, where AI functions as a semi-independent regulator, is the application of AI used to detect malicious messages and inappropriate material on social networks or the use of AI in selecting specific content for social network users [8]. This example does not constitute a significant security threat to the rule of law, but it proves the potential of Al to act in a regulatory manner. It is fair to say that Al can „participate in people’s social life, shape it, and influence people’s choices in the social sphere.“ [6] For example, Al is used extensively as part of filtering algorithms on various social media. It filters the content and decides what information is available to the users. This, in principle, threatens freedom of speech. As a result, the unregulated use of Al has the potential to threaten democratic regimes and, in some cases, even the rule of law – if similar algorithms were used, for example, for processing the materials in the judiciary.

The potentially harmful activities of Al-powered algorithms are not limited to social media. Increasingly, they are being used in more fundamental sectors such as law, education, or law enforcement. Al can, for instance, be used in DNA analysis, the creation of educational materials, or for summarization of evidence in legal cases. [9] Possible manipulation or selective data use in any of the mentioned environments could harm individuals and societal development. To be concise, Al could determine the course of events by manipulation while being aware of the lack of accountability for its actions.

One key aspect of Europe is industrial sovereignty. Cooperation between European and non-European companies, startups, and large foreign companies in Al development is essential. [10] Nonetheless, the institutional centralization and monopolization of Al’s development outside of Europe is a risk and if not adequately addressed, it could threaten the interests of Europe and its citizens. In order to protect those interests and ensure overall safety and reliability while using Al, Europe needs to be sovereign and efficient in developing its own Al models, while not being isolated from the rest of the world. Having proper control over the development, application, and activities of Al is the first premise for ensuring that Europeans are not threatened by Al.

Al system activity control is another critical premise for maintaining safe and reliable Al in Europe. It is especially relevant if Al potentially evolves beyond its current narrow form. For this and other reasons, the European Al Act requires a physical person to supervise Al systems. [1] In this respect, the content of the regulation is relevant. Combined with the sovereign European Al development, considering the European regulation, it forms a solid foundation for safe Al use in Europe. Despite that, it is still necessary to address the persistent problem of the need for more relevant data to assess whether the current scope of regulation is adequate.

Dual Use of AI

The second dimension concerns the use of Al applications as tools. In the context of global competition for Al development, the application of Al in civilian environments is gradually becoming a standard. According to available data, in 2023, 35% of industries had used Al in some form for their business activities. [11] Based on simulations, this share is expected to rise to 70% by 2030. [12] With the increasing presence and number of applications of Al systems, the potential for misuse is also growing. Today, we are witnessing the use of generative Al, for example, to conduct relatively simple cyber-attacks. Due to the misuse of Al, such attacks are becoming more accessible and, therefore, more frequent. [13]

The problem with misusing Al as a dual-use technology begins with prevention. The first step, limiting the proliferation, is some form of regulation. However, the regulation of Al technology is complex. Al possesses characteristics that make regulation and its enforcement highly challenging, and in some cases, even impossible. First, the natural complexity and variability of the Al systems complicate the efforts to classify their misuse potential. Second, the easy transferability of systems across borders and the difficulty of monitoring target users, especially in the case of publicly available systems using Al, pose a significant challenge to any regulator. The widespread availability of general-purpose AI programs renders general-purpose software controls for these systems largely ineffective. Moreover, any meaningful regulation might be dismissed due to its potential to „harm the US, EU or Chinese technology sectors if they inhibit exports for commercial applications“ [14].

The increased risk of abuse shows, among other things, one of the fundamental reasons why effective domestic AI research and application are essential for Europe. Assuming it is impossible to effectively control the movement of potentially harmful AI assets, the only option is to mitigate their impact. This can be achieved primarily by increasing resilience through the development of domestic systems, which also makes Europe independent of non-European AI sources. If Europe cannot develop and operate its own high-quality AI systems, it will compromise the security of European citizens, businesses, and institutions, either because of a lack of protection or by creating a forced dependency on non-European systems.

Emerging Threats in the Shadow of AI as a Military Asset

AI is an asset with significant military-political-strategic value. Beyond its potential to increase production and efficiency, AI also brings a range of military applications and new threats. In this way, AI „constitutes the upcoming revolution in military affairs that may redirect the relative distribution of power.“ [31] Moreover, the new threats become even more serious when considering the high complexity of controlling the proliferation of AI assets and their dual-use potential, increasing the risk of misuse.

The application of AI will affect all areas of security to some degree, and in some, AI can have a particularly significant impact. This phenomenon is most visible in the fusion of AI and cybernetics. Today, AI is used to detect phishing, malware, or ongoing cyber-attacks. [16] AI’s most significant current challenge in cybernetics is to increase resilience „against the adaptive behaviors of the adversaries.“ [24] Machine learning, as the most commonly used AI tool in cybernetics today, cannot reliably predict changes on the side of attackers and is therefore ineffective in defending against ongoing cyber-attacks. Nevertheless, this may change with the application of more advanced AI systems with better „improvisation capabilities.“ We must consider that those AI tools will „equally empower offensive and defensive measures.“ [24] Still, thanks to the absence of human error, AI will allow us to counter any threats in cyberspace more effectively. Of course, we cannot expect cyber-attacks to disappear. AI systems capable of conducting attacks independently are already under development. [16] If applied through adaptive systems capable of improvisaton, this would pose a significant problem for the present form of cyber defence. According to a 2019 Forrester Research report, three-quarters of surveyed cybersecurity decision-makers at global enterprises expect an increase in the scale and speed of new attacks, and 66% expect the emergence of new attacks that no human could create, which makes AI-based cyber protection more of a necessity than just a choice. [15]

Europe has long been one of the main targets of cyber-attacks, and the quantity might increase even more due to various events. For example, with the conflict in Ukraine, EU states have registered a significant increase in cyber-attacks during the six-month period between 2022 and 2023. Of all attacks worldwide, the proportion of targets located in EU states increased from an initial 10% to 50% during this period. [17] Assuming a similar scenario might occur in an environment where advanced AI is available by default, the ratio could be even higher, the attacks more effective, and the consequences way more severe, especially if Europe were unable to use AI for its defence.

Regarding cybernetics, Russia is a traditional adversary of Europe. The Russian military emphasizes AI’s importance primarily as a military tool. [18] Although the war in Ukraine has temporarily weakened the current Russian military-technological complex, the threat of traditional cyberattacks has not diminished, and future applications of AI will only heighten this threat. Successfully countering Russia’s increasing cyber aggression requires strengthening the EU’s political decision-making. [19] Only then can Europe effective develop the necessary tools (including cyber-AI tools) to respond to hostile activities in cyberspace on time and to the greatest extent possible. If Europe fails in this respect, the resilience of European cyberinfrastructure will drop significantly. In other words, in the event of an all-out war or other severe circumstances, Europe will have difficulty defending itself in cyberspace.

Beyond cyber, AI also plays a vital role in information warfare, and most actors active in AI development have noticed this shift in the security environment. China, for example, has articulated its expectation of a transition from today’s information warfare to „intelligenized warfare“ (智能化战争). [20] It’s impossible to make a clear distinction between information warfare and „intelligenized“ warfare, as the disciplines complement each other and form a coherent system. The application of AI brings many new possibilities to the field of information warfare. One of the most profound recent examples is the use of generative AI to „create“ information, such as high-quality deep fakes, which are already often as convincing as authentic material. [21] Moreover, there is no reason to expect a decline in the sophistication and quantity of those materials.

The creation of AI deepfakes takes mere seconds, minutes at most, and can be done by virtually anyone. A glimpse of this issue can be seen, for example, in Opens AI’s recently introduced text-to-video AI model, Sora, which makes relatively trustworthy up to one-minute-long videos on any given topic [32]. Combined with other AI models, it is a very effective tool for spreading misleading information, possibly leading to public opinion manipulation, violence-inciting, or creating societal chaos supported by the unreliability of informational intake.

The only realistic way to reduce the effectiveness of AI-created deepfakes is to use AI for their detection. Current AI tools designed to detect them are far from reliable, but soon, it might be an indispensable weapon in this fight. For example, AI can uncover deepfakes by finding patterns in which fake news spreads [22] or by detecting common markers in posts that indicate identical artificial origins. [23] Such defensive AI tools are an absolute necessity for maintaining European societal resilience. Especially given the continuous intent of the Russian Ministry of Defense to apply its vision of militarized AI [18], which will enable Russia to streamline the hybrid operations already underway in Europe.

Beyond use for hybrid warfare, AI is also potentially useful for “standard“ strategic and tactical warfare purposes. Although technologies alone do not win wars, they function as effective force multipliers, which is also true for AI. [25] Soon, robotics with applied AI will likely become the standard means of defence. Such machines have the potential „to manoeuvre faster and employ force with more precision than those operated by humans.“ [26] Currently, the first experiments demonstrating AI’s ability to surpass human operators‘ capabilities are emerging. [27] [28] Most of these experiments have been conducted in the air domain, possibly due to the absence of terrain and obstacles, which reduces the need for improvisation, unlike ground-based simulations, where humans still have the upper hand. However, this could change once AI can apply human approaches and combine them with its computational capacity and efficient data collection. At that point, the possibilities for specific applications would be practically limitless. A good example is AI’s capability to enhance the performance of air defence systems. [29] Attacks on civilian and military infrastructure conducted from the air have recently become one of the most frequently used methods of warfare. While AI cannot entirely prevent these attacks, it can help significantly reduce the amount and extent of potential damage.

Hand in hand with the application of AI comes the increased efficiency in data and information collection and their processing for operational and strategic purposes. AI can be used to reduce the time it takes to complete the OODA cycle (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). Utilizing AI would help outperform the enemy’s decision cycle or achieve strategic parity in case enemies use the AI for the same purpose. Thus, it is essential to understand that AI is not only a means of establishing dominance but also a means of ensuring strategic balance.

Regarding the quality of decision-making, AI is also potentially useful for combining high computing capacity with a more human-like approach to problem-solving. AI enables the processing of Big Data, or information arriving in real-time and in such large quantities that it is unprocessable by a single computer.This volume of data makes it difficult for humans to use all available information and find solid relationships between incoming inputs. If AI masters the inreicacies of human approaches to information processing, it could compile Big Data from diverse sources similarly to how humans would, if they had the capacity to do so. [30] Additionaly, AI excels in improving performance in data collection, which can serve as a solid foundation for better situational awareness or targeting and, therefore, improving the informational environment for decision-making. [29]

The implementation of AI can also radically transform intelligence work. [31] AI can be used to process large amounts of data from publicly available sources and connect them with other types of available information, leading to higher-quality intelligence outputs. To illustrate, AI can help find patterns of behaviour present in image intelligence sources, or it can filter and classify the relevance of social media posts for open-source intelligence.

The list of potential AI applications for defence and security purposes extends far beyond those listed in this article. As demonstrated, AI applications are relevant to both non-military and military security. Military AI applications have considerable potential. However, their implementation requires „significant investment to ensure military-grade safety and trust.“ [25] Ignoring this need for investments to develop reliable and safe AI may lead Europe to a dead end, where it is either unable to use AI effectively or becomes dependent on non-European systems. Indeed, the absence of AI application, with a consequent stagnation in the potential performance of European armies, will negatively affect deterrence capabilities.

A Threat and a Necessity for Europe

An apparent relationship exists between the development and application of AI and its potential to reshape the security environment. The falsification of information, AI-based military threats, misuse of civilian-grade AI for malicious purposes, and the undermining of the rule of law and the stability of democratic regimes through AI are all real threats that Europe will face in the near future.

AI represents another significant leap in information management and has the potential to transform how security is ensured and maintained. It is both a necessary and potentially dangerous tool, placing Europe in a delicate position. To mitigate any dangers of AI, Europe must develop reliable, safe, and efficient AI withing the framework of current European regulations. Achieving this will require a unified European stance on AI development, supported by broad and unbiased acceptance of what AI can and will bring, including both positives and negatives.

Whether we like it or not, AI will play an essential role in the future. For most international actors, including potential European adversaries, AI is perceived as a critical tool for security and defence. While Europe is not in immediate danger, this could change rapidly as AI becomes more deeply integrated into society and military affairs. AI is not just another force multiplier in warfare or a tool increasing industrial production efficiency. It is likely to present an existential problem in the future, and Europe must prepare for this shift in the security environment.

Article reviewed by Michaela Doležalová and Dávid Dinič

Sources

[1] European Parliament. (2023, August 6). EU AI Act: First Regulation on Artificial Intelligence. European Parliament Last visited on July 22, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence .

[2] Dinh, J. (2022). How Will We Know When Artificial Intelligence Is Sentient? Discover Magazine. Last visited in July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.discovermagazine.com/technology/how-will-we-know-when-artificial-intelligence-is-sentient.

[3] Buyruk A. I. E. & Tudor C. (2023). Will an AI ever become conscious?. Keysight. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.keysight.com/blogs/tech/2023/05/05/will-an-ai-ever-become-conscious.

[4] European Union. (2024). Aims and values. Euroepan Union. Last visited in July 23, 2024. Retrieved from:https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/principles-and-values/aims-and-values_en.

[5] Rosengrün, S. (2022). Why AI is a Threat to the Rule of Law. Digital Society, 1 (2), 1-15. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44206-022-00011-5.

[6] Mocyuk E. & Plosyajczak B. (2020). Artificial Intelligence – Benefits and Threats for Society. Humanities and Social Sciences, 27 (2), 133-139. Retrieved from: http://doi.prz.edu.pl/pl/pdf/einh/565.

[7] Huddleston J r. T. (2023). ‘Godfather of AI,’ ex-Google researcher: AI might ‘escape control’ by rewriting its own code to modify itself. CNBC. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/10/11/tech-godfather-geoffrey-hinton-ai-could-rewrite-code-escape-control.html.

[8] Clegg, N. (2023). How AI Influences What You See on Facebook and Instagram. Meta. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://about.fb.com/news/2023/06/how-ai-ranks-content-on-facebook-and-instagram/.

[9] Rigano Ch. (2020). Using Artificial Intelligence to Address Criminal Justice Needs. NIJ Journal, 280, 1-10. Retrieved from: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/252038.pdf.

[10] Meltzer J. P., Kerrz C. and Engler A. (2020). The importance and opportunities of transatlantic cooperation on AI. Brookings Insttitution. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AI_White_Paper_Submission_Final.pdf.

[11] Wardini, J. (2024). 101 Artificial Intelligence Statistics. TechJury. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from:https://techjury.net/blog/ai-statistics/.

[12] Pwc. (2023). PwC’s Global Artificial Intelligence Study: Sizing the prize. PwC. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/data-and-analytics/publications/artificial-intelligence-study.html.

[13] Mascellino, A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and USBs Drive 8 % Rise in Cyber-Attacks. Infosecurity Magazine. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/news/ai-usbs-drive-rise-cyber-attacks/.

[14] Carrozza, I., Marsh, N., & Riechberg, G. M. (2022). Dual-Use AI Technology in China, the US and the EU: Strategic Implications for the Balance of Power. In Peace Research Institutte Oslo (pp. 1–43). PRIO. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://cdn.cloud.prio.org/files/6c0dc6db-c6b3-44a4-b775-126ff97588b4/Carrozza%20Marsh%20Reichberg%20-%20Dual-Use%20AI%20Technology%20in%20China%20the%20US%20and%20the%20EU%20-%20Strategic%20Implications%20for%20the%20Balance%20of%20Power%20PRIO%20Paper%202022.pdf?inline=true.

[15] Forrester. (2020). The Emergence of Offensive AI Get started How Companies Are Protecting Themselves Against Malicious Applications of AI. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.snowdropsolution.com/pdf/The%20Emergence%20Of%20Offensive%20AI.pdf.

[16] Keysight Technologies Romania. (2023, April 26). Poate Inteligența Artificială Să Devină Conștientă? | Keysight Technologies Romania. YouTube. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfmdOqVm6Qs

[17] Thales. (2023). From Ukraine to the whole of Europe:cyber conflict reaches a turning point. Thales Group. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/worldwide/security/press_release/ukraine-whole-europecyber-conflict-reaches-turning-point.

[18] Thornton, R., & Miron, M. (2020). Towards the ‘Third Revolution in Military Affairs’: The Russian Military’s Use of AI-Enabled Cyber Warfare. The RUSI Journal, 165(3), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2020.1765514.

[19] Limnell, J., Alatalu, S., Borogan, I. et al. (2018). Russian cyber activities in the EU. In N. Popescu & S. Secrieru (Eds.), HACKS, LEAKS AND DISRUPTIONS: RUSSIAN CYBER STRATEGIES (pp. 65–74). European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21140.10.

[20] PRC State Council. (2019). 新时代的中国国防. www.gov.cn. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from:https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-07/24/content_5414325.htm.

[21] Myers, A. (2023). AI’s Powers of Political Persuasion. Stanford HAI. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://hai.stanford.edu/news/ais-powers-political-persuasion.

[22] Cassauwers, T. (2019). Can artificial intelligence help end fake news? Ec.europa.eu. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/can-artificial-intelligence-help-end-fake-news.

[23] Pacheco, D., Hui, P.-M., Torres-Lugo, C., et al. (2021). Uncovering Coordinated Networks on Social Media: Methods and Case Studies. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 15 (1), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v15i1.18075.

[24] Davis, Z. (2019). Artificial Intelligence on the Battlefield: Implications for Deterrence and Surprise. PRISM, 8 (2), 114–131. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26803234.

[25] Shetty, D. K., Prerepa, G., Naik, N., Bhat, R., Sharma, J., & Mehrotra, P. (2023). Revolutionizing Aerospace and Defense: The Impact of AI and Robotics on Modern Warfare (Vol. 19, pp. 1–8) [Review of Revolutionizing Aerospace and Defense: The Impact of AI and Robotics on Modern Warfare]. Association for Computing Machinery. https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.1145/3590837.

[26] Payne, K. (2018). Artificial Intelligence: A Revolution in Strategic Affairs? Survival, 60 (5), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1518374.

[27] Karlík T. (2023). Dron řízený umělou inteligencí porazil lidské piloty. Podle vědců je to mezník. ČT24. Last visited on July 23, 2024. Retrieved from: https://ct24.ceskatelevize.cz/veda/3616138-dron-rizeny-umelou-inteligenci-porazil-lidske-piloty-podle-vedcu-je-meznik.

[28] Ernest, N., & Carroll, D. (2016). Genetic Fuzzy based Artificial Intelligence for Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle Control in Simulated Air Combat Missions. Journal of Defense Management, 06 (01), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0374.1000144.

[29] Davis, Z. (2019). Artificial Intelligence on the Battlefield: Implications for Deterrence and Surprise. PRISM, 8 (2), 114–131. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26803234.

[30] Morgan, F. E., Boudreaux, B., Lohn, A. J., Ashby, M., Curriden, C., Klima, K., & Grossman, D. (2020). Military Applications of Artificial Intelligence: Ethical Concerns in an Uncertain World. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3139-1.html.

[31] Копаня М. В. (2023). Artificial intelligence and international security: The upcoming revolution in military affairs. Sociološki Pregled, 57 (1), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.5937/socpreg57-43012.

[32] OpenAI. (2024). Sora: Creating video from text. OpenAI. https://openai.com/sora.