Caspian Sea has been drawing quite a lot of attention in recent years, mainly because of immense reserves of fossil fuels. Crude oil and natural gas from Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Azerbaijan flows into many parts of Eurasian space and contributes to the energy mix of countries such as Italy, Turkey or China. This region is a closely watched space, because the smaller states on the banks of Caspian Sea are emerging as significant oil and gas powers, in terms of reserves comparable to Russia, Saudi Arabia or the United States.

In this article, the Caspian Sea has a role of a common denominator for these countries, as it has been a source of wealth through hydrocarbons, but also a source of territorial disputes. This article aims to compare the oil and gas production approaches of the aforementioned countries and find out, whether the region is stable and unified or whether it is divided into smaller notional parts influenced by international relations, business or internal politics. For each country there is an energy profile created and these profiles are then compared to achieve some sort of a complex picture of this region.

Russia

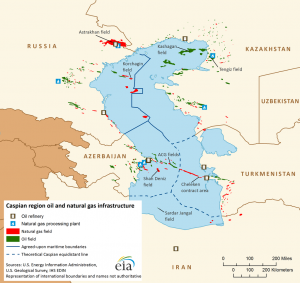

The Russian Federation, located on the north-western bank of the Caspian Sea, is one of the strongest players in hydrocarbon production. Russia delivers large volumes of both oil and gas to Europe and Asia, using a dense network of pipelines dating back to the times of the USSR, but also state-of-the-art systems, such as Nord Stream, Blue Stream or Power of Siberia. In the Caspian Sea region, Russia is not as active as in other parts of the country. The largest oil and gas companies, such as Lukoil or Gazprom run a few oil and gas fields, but with quite small output. Lukoil, the largest Russian private company, states that its activities in the Caspian Sea include three main fields, namely Yury Korchagin, Vladimir Filanovsky and Valery Grayfer [1]. The first two fields are already producing, Grayfer is still in development. In a press release from December 2020, Lukoil mentions that in 2020 it produced over 7 million tonnes of oil from the Korchagin and Filanovsky fields [2]. To put it in perspective, Russian Ministry of Energy states that in 2020 the overall oil production measured almost 513 million tonnes of oil [3]. The Caspian Sea cannot compare to the large fields in northern Russia or in Western Siberia, but the ongoing development of the fields is a sign that Russia is counting on these projects in long-term plans.

Gazprom, the largest state-owned Russian company, has a different position in the Caspian Sea region. Basically, the only active field is the Astrakhanskoye field near the city of Astrakhan, which is fairly minor field, considering the megaprojects on the Yamal Peninsula or in the Barents Sea. More interesting is Gazprom’s cooperation with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. While the Astrakhanskoye field cannot be found on the company’s website apart from few mentions in press releases, development of Tsentralnoye and Imashevskoye fields is well presented. These two projects have two main operators. On the Kazakh side, there is KazMunayGas National Company, the main gas producer in Kazakhstan. Russian side is made up by TsentrCaspneftegaz, which is a company set up by Lukoil and Gazprom. Both countries have 50% share in the project, which means Gazprom’s stake is 25% [4]. These two projects are Gazprom’s main involvement in the Caspian Sea. Apart from that, there are two projects in Uzbekistan, namely Shakhpakhty and Dzhel in the Ustyurt region. Both fields are located in the western part of Uzbekistan and since 2002, Gazprom cooperates with Uzbekneftegaz on the development of the region [5].

Azerbaijan

Historically important fossil fuel producer, Azerbaijan is one of the main producers of oil and gas from the offshore fields. The Azeri-Chinag-Gunashli (ACG) oilfield is the main offshore oilfield in Azerbaijani waters. Since 1997, it is operated by the Azerbaijani International Operating Company, which is a consortium made up by foreign energy companies, where most of the shares is held by British Petroleum [6]. Other notable companies include American Chevron, Norwegian Equinor and Japanese INPEX. The State Oil Company of Republic of Azerbaijan, SOCAR, holds 11% of shares [7]. This system is quite characteristic for Azerbaijan, as the other fields are operated on a similar basis, that is through production sharing agreements (PSAs) with foreign countries. In this aspect, the Azerbaijani energy sector is much more open to foreign investment, while maintaining the state presence in these agreements through the state-owned SOCAR.

Another key field is the giant Shah Deniz natural gas field. Shah Deniz (King of the Sea) is again operated on the PSA basis and major stakeholders are British Petroleum and Equinor. Minor stakeholders include French Total, Russian Lukoil and SOCAR [8]. Natural gas from this field is transported into Europe via Southern Gas Corridor. This corridor runs through Georgia, Turkey, and Greece into Italy, where it connects to the existing pipeline network. One of the results of orienting its export towardsEurope is getting into a competition with Russia. The Southern Gas Corridor completely bypasses Russia and allows the EU states to lower their dependence on Russian-operated pipelines. This presents a significant boost to the energy security of Europe.

Iran

Iran was the third largest natural gas producer in 2019 and the fifth largest oil producer among OPEC countries in 2020 [9]. However, most of its fields lie in the south of the country, around the Persian Gulf. Iran states that only one field is present in the Caspian Sea, the Sardare Jangle gas field. It is however a minor field compared to other Iranian gas fields, such as South Pars/North Dome, the largest natural gas field in the world, whose ownership is divided between Iran and Qatar. Sardare Jangle is currently in the exploration phase, but there are hopes it can boost the growth of the Iranian northernmost regions in the Caspian Basin.

Iranian oil and gas is managed by a state-owned National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), which oversees production and development of all the fields. In this aspect, oil and gas industry is rather closed, in contrast to foreign involvement in other Caspian Sea states. Iranian production suffers from ongoing US sanctions, but in recent news, the state decided to increase the production nonetheless [10]. This example shows how oil and gas trade is relevant in world politics. It might also be a reason to develop new fields, to keep the levels of production with possible additional increases when the political situation needs them. However, for Iran, the Caspian Sea is still a much underdeveloped part of hydrocarbon supply chain.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan is one of the main exporters of natural gas to China. This sparsely populated arid country is home to large volumes of natural gas, all of which comes from either the Caspian Sea or the Caspian Basin, so there is both offshore and onshore extraction. Even though the population of Turkmenistan is only slightly over 6 million, the country holds the fourth-largest proven reserves of natural gas in the world [11].

Because of its landlocked position, the country relies on pipelines rather than transport of LNG (liquified natural gas) via maritime routes. In this aspect, the geographical location is suitable, as there are multiple pipelines in its territory. Turkmenistan exports its commodities both eastwards and westwards. It is connected to Central Asia-Center gas pipeline system (CAC) which also distributes gas from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Russia and then further west. This pipeline transfers gas from Daulatabad gas field [12]. Another route leads to China via Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline (CACG), originating in eastern part of Turkmenistan, running through Uzbekistan and southern Kazakhstan into Chinese Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region [13]. This pipeline draws gas from major Central Asian fields, such as Galkynysh (Turkmenistan), Karachaganak or Tengiz (both Kazakhstan). The last route is more of a project because it is a proposed TAPI pipeline, stretching from Turkmenistan, through Afghanistan and Pakistan into India. This is however still in a development phase, as there remains significant progress to be made.

Oil and gas in Turkmenistan is managed by two state-controlled companies, Turkmengaz and Turkmenneft. There is also a small involvement from foreign companies, such as Chinese CNPC or Dragon Oil of United Arab Emirates, in a form of Production Sharing Agreement [14].

Kazakhstan

Finally, the last country in this article is Kazakhstan. It is home to the giant Tengiz oil and gas field, as well as Karachaganak and Kashagan fields. Kashagan is described as the largest known oil field outside of the Middle East [15]. Kazakhstan follows the model used by for example Azerbaijan when it comes to managing its natural resources, that means extensive cooperation with foreign companies, while also participating through a state-controlled company, in this case KazMunayGas. There is a joint venture called the North Caspian Operating Company, which includes Eni, KazMunayGas, Total, Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, CNPC and INPEX, and operates the Kashagan field [16]. Tengiz is operated by US Chevron, ExxonMobil, KazMunayGas and Russian Lukoil. Finally, Karachaganak field is managed by British Gas, Eni, Chevron, Lukoil and KazMunayGas. Event though that is a lot of foreign investment, Kazakhstan still has control in all of its assets.

When exporting its resources, Kazakhstan combines pipeline transport with LNG carriers. The western markets are supplied via Central Asia-Centre gas pipeline system, as mentioned before, but Kazakh oil and gas is also shipped via tankers to Baku in Azerbaijan, where it is loaded into Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. There is also a pipeline to China, which originates in Turkmenistan and goes through south-east Kazakhstan and another Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline supplying the oil from Tengiz field. The Tengiz field is connected to both westwards and eastwards pipelines, while gas from Kashagan and Karachaganak is supplied mainly to China. [12]

Comparison

Now, to be able to compare the energy profiles of all the countries, we must choose certain aspects to compare. In this case, it is a form of management of the resources, that means whether the state allows foreign companies to operate. Next it is the orientation to eastern, western or both markets. It is also a question whether the Caspian Sea is a key region for the extraction in the country.

Let’s start with the two largest states, Russia and Iran. These countries have quite a lot of similarities. Firstly, their approach to Caspian Sea is quite laid-back, as they both have far more important regions with incomparable amount of oil and gas. Still they show some activity in the Caspian Sea, as it is a perspective prospect in the future. Both countries show strong control of the state, with Russian Lukoil being the exception, as it is a publicly traded company. The difference is that while Iran contributes next to nothing in terms of transportation of oil and gas the region, Russia is a key partner for basically every other state around the Caspian Sea. Pipelines from Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan use Russian territory to market their resources to Europe.

The three remaining countries are slightly more difficult to compare as they have both similarities and differences in key areas. Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan share a form of operating the fields. Both states implement strong foreign involvement, which brings many world-class companies and their capital into the region. Cooperation with energy giants such as Chevron, Equinor or British Petroleum helps with funding both upstream (eg. drilling, extraction and exploration) and downstream (eg. refining and transporting) projects and the high revenues are hard to overlook when visiting capitals Baku or Nur-Sultan. Turkmenistan is an exception here as it basically retained the structures from the Soviet Union era and the majority of operations is state-controlled via Turkmengaz and Turkmenneft, with only a minor involvement from foreign companies.

It is also difficult to state their market orientation. All three states export to western and eastern markets, but there are of course some distinctions. Turkmenistan is the main supplier of natural gas to China and the CACG pipeline system has four different lines all leading to the world’s largest energy consumer [17]. It is also connected to the CAC system to Russia, so the western market is accessible, although probably not aseasily as China. Kazakhstan stands somewhere in the middle, as it also supplies China with oil, but at the same time large volumes of fossil fuels are shipped to Russian pipelines or delivered to Baku via LNG carriers. The last country, Azerbaijan, is oriented mainly towards Europe. With the completion of the Southern Gas Corridor, it is no longer dependent on Russian transfer, although it still sends some oil and gas this way. Azerbaijani oil is a key in diversification of sources for some European states, for example the Czech Republic, where Azerbaijan is the second largest oil supplier after Russia [18]. It can also be noted that while Azerbaijan relies heavily on the offshore extraction, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan produce more from onshore fields, even though offshore is gaining momentum.

Conclusion

In the Eurasian space, Central Asia has become a significant producer of oil and gas and the littoral states of the Caspian Sea benefit greatly from this industry. The countries share some similarities, but overall they should not be regarded as one larger complex, as they are quite diverse. There are significant differences in managing natural resources, as well as market orientation. Even then, there is still quite heavy regional cooperation, as the shared pipeline system or transport system in general benefits all the actors and brings capital into places where it is .

List of sources

- „Growth Projects“. com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.lukoil.com/Business/Upstream/KeyProjects

- (2020). „Thirty Five Million Tonnes Of Oil Produced At Lukoil’s North Caspian Fields“. com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.lukoil.com/PressCenter/Pressreleases/Pressrelease?rid=509957

- Ministry of Energy of Russian Federation. „Statistics.“ ru. [online] Retrieved from: https://minenergo.gov.ru/en/activity/statistic

- „Kazakhstan.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.gazprom.com/projects/kazakhstan/

- „Uzbekistan.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.gazprom.com/projects/uzbekistan/

- (2016). „SOCAR and BP-operated AIOC sign principles of agreement on future development of the ACG oil field in Azerbaijan to 2050.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/news-and-insights/press-releases/socar-and-bp-operated-aioc-sign-agreement-on-future-development-of-acg-oil-field-in-azerbaijan-to-2050.html

- „Azeri Chirag Deep Water Gunashli.“ az. [online] Retrieved from: https://socar.az/socar/en/company/production-sharing-agreements-offshore/azeri-chirag-deep-water-gunashli

- „Shah Deniz.“ az. [online] Retrieved from: https://socar.az/socar/en/company/production-sharing-agreements-offshore/shah-deniz

- S. Energy Information Administration. (2021). „Country Analysis Executive Summary: Iran.“ gov. [online] Retreived from: https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Iran/pdf/iran_exe.pdf

- Hafezi, Parisa. (2021). „Iran determined to increase its oil exports despite U.S. sanctions -oil minister.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-determined-increase-its-oil-exports-despite-us-sanctions-oil-minister-2021-09-01/

- Gill, Chris., & Pollard, Jim. (2021). „China turns to Turkmenistan for gas, thumbs nose at Australia.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.asiafinancial.com/china-turns-to-turkmenistan-for-gas-thumbs-nose-at-australia

- S. Energy Information Administration. (2013). „Overview of oil and natural gas in the Caspian Sea region.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/regions-of-interest/Caspian_Sea

- „Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline.“ cn. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.cnpc.com.cn/en/CentralAsia/CentralAsia_index.shtml

- S. Energy Information Administration. (2016). „Turkmenistan.“ gov. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/TKM

- S. Energy Information Administration. (2019). „Background Reference: Kazakhstan.“ gov. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Kazakhstan/background.htm

- Batyrov, Azamat. (2021). „Kazakhstan Launches Construction of Gas Plant at Giant Kashagan Field.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/kazakhstan-launches-construction-of-gas-plant-at-giant-kashagan-field-2021-6-14-0/

- Zhang, Rachel. (2021). „China looks to Turkmenistan for more gas as it cuts Australian supplies.“ com. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3133084/china-looks-turkmenistan-more-gas-it-cuts-australian-supplies

- Tramba, David. (2019). „Méně závislosti na Rusku. Podíl nakoupené ropy klesl na 45 procent.“ cz. [online] Retrieved from: https://www.euro.cz/byznys/mene-zavislosti-na-rusku-1472401